Today, let's ride on the railroad. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Do you remember the song,

Ol' clickety clack,

Comes echoin' back,

The Blues in the Night.

Do you remember the melancholy of trains bearing us away over the great sprawl of Mid-America? I can still taste the crawling despair that closed me in as I rode the train from college in Seattle to Basic Training in Virginia. I thought, then, that nothing worse would ever befall me. Maybe trains were melancholy because they gave us so much more time to think than airplanes do.

Yet those old machines rode with a simple rough-hewn majesty. In 1855, Walt Whitman wrote To a Locomotive in Winter:

Type of the Modern -- emblem of motion and power --

pulse of the continent,

Law of thyself complete, thine own track firmly holding,

Thy trills of shrieks by rocks and hills return'd,

Launch'd o'er the prairies wide, across the lakes,

To the free skies unpent and glad and strong.

The steam locomotive was so evocative. Trains shaped our nation psychically at the same time they shaped us physically.

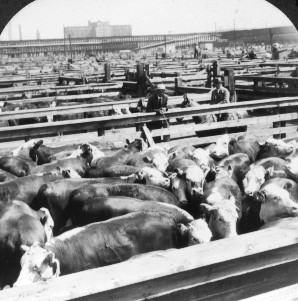

Look at Chicago. Railroads made that city. Chicago wasn't much when we began running cattle on the great plains.

First we'd load livestock on trains and send them East. They rode the old cattle cars with slatted open sides. They'd arrive hungry, thin -- sometimes even dead. So we developed special fast trains for livestock. Next we created "humane" cattle cars with feed trays and water troughs.

All the while, Chicago laid claim to that trade. By the Civil War, Chicago was the greatest rail yard in the world. Then, in 1880, rail technology changed the game again. That's when refrigerated cars came into use. Now we could slaughter animals in the West. Now we could ship carcasses to the packing houses. And Chicago became, in Carl Sandburg's words, "hog butcher for the world."

So specialized rolling stock changed American commerce. We saw live poultry cars, ore cars, even pickle and vinegar cars.

And I'd go down to the tracks behind the house. I'd lay a penny on the track, hunker in the bushes, and study the mighty thunder of passing cars. At last I'd stand, wave at the flagman in the caboose, and retrieve my penny -- now squashed to the diameter of a demi-tasse saucer.

Why do trains speak the melancholy of separation and loss so eloquently? In the end, I suppose it is the loss of childhood that I grieve when I recall those great screaming, roaring, hissing engines -- of so long ago.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

White, J.H., Jr., Changing Trains. American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Vol.7, No.1, Spring/Summer 1991, pp. 34-41.

The Walt Whitman poem is taken from: Whitman, W., The Leaves of Grass. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., Inc., 1940, p. 286.

Image courtesy of Margaret Culbertson

Great Union Stock Yards in the early 20th century,

largest Stock Market on Earth, Chicago, IL

Photo by John Lienhard

And today, we go to model railroad builders to find scenes like this.