1900

Today, a magazine looks at the century past, and the one to come. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I'm reading a 1900 magazine, The World's Work. First, book reviews: Conrad's Lord Jim, they say, is told "with remarkable literary art." Alice of Old Vincennes is "a cheerful book of action, of little literary art and no permanent value, but a rattling story for a passing day." Not-yet-president Theodore Roosevelt's biography of Oliver Cromwell is "attractive less for its literary quality than for its direct grip in the larger aspects of his subject."

A year later we'd make that Rough-Rider our president, exactly because of his grip on the larger aspects. And we're reminded that the bespectacled Teddy Roosevelt was a serious scholar.

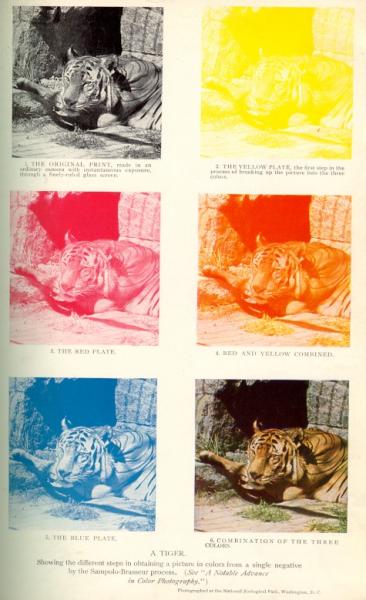

America had recently carved out her place as an industrial power. Now she was establishing herself as a political power and as an inventive power. Another article describes "A notable Advance in Color Photography." We're told,

It is now possible [to take a snapshot in China with an] ordinary camera fitted with a newly perfected screen, to send the negative to New York, and there have the picture reproduced in all its original colors, ...

The negative in this Brasseur/Sampolo process has tiny horizontal strips. Each strip reproduces one primary color, red, yellow, and blue. When the strips are superposed they give the image. This is the first color photography fast enough to record moving subjects. Rudimentary color photography had been around since the 1850s. But it wouldn't be on the market until 1907. It wouldn't be commonplace until the '30s. This is a way-station in that evolution.

Another article casts 19th-century political changes as a struggle between liberalism and nationalism. The century began with Napoleon's conquests. Smaller countries reacted by forging a new concept of national unity. The scattered German and Italian states had each banded into unified nations. But the other protection against forces of conquest was the voice of a free people. Liberalism rose up after mid-century, only to be drowned out at the century's close by voices of national interest and land-grabbing.

Another author asks, "Are young men's chances less?" Business had grown into such a monolithic force by 1900 that it threatened to block the next generation. The author doesn't see that the young who'll go far will do it by riding the fast horse of emergent technology. Henry Ford was only 36. The Lockheed brothers were young. The new pioneers of radio, automobiles, and flight would all be drawn from the ranks of the young.

This old magazine offers a touching view of people peering into the darkness of a future wreathed in change too rapid to handle. It's a view of ourselves as we stand on the threshold of the 21st century. Now, as then, technology is the wild card in a game of poker we're bound to play through to some unexpected outcome.

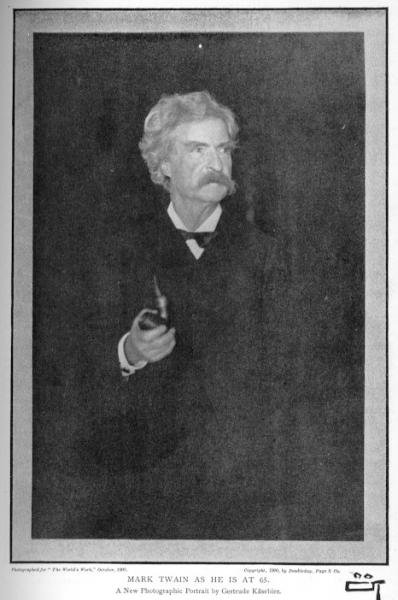

One last article sums it up. Mark Twain, at 65, has everyone terrified. He claims he's writing his opinions of all his contemporaries in an article not to be published -- until a century hence.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The World's Work, various articles, November and December, 1900.

From The World's Work, 1900. Click on the thumbnail above to see the full image

Left: Brasseur/Sampolo process. Right: Mark Twain at 65.