C Rations

Today, an army tries to travel on its stomach. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Tuesday, 1954, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Four of us set out for a German restaurant in nearby Long Branch. We called this our Eine Kleine Knockwurst evening. Each Tuesday the Army served C rations in the mess hall. Each Tuesday we went off to buy our own supper. For who would be caught dead eating C Rations?

C rations consisted of canned meat and vegetables, packed in preservatives, along with hard biscuits. Your stomach soon began to seize up at the sight of those olive drab cans. C rations provided 3800 calories a day in battle conditions when it wasn't possible to set up a mess hall. The army had to keep an inventory of the stuff, and its shelf-life was limited. So at the end of that shelf life, the troops either ate it or let it cycle into the trash bin while they hitch-hiked into town for real food.

Barbara Moran tells how the problem of feeding troops in the field has haunted armies. Civil War soldiers carried a water-and-flour biscuit called hardtack, and they constantly suffered scurvy. The Army introduced the C ration, or combat ration, in 1938. At first, a day's portion added almost six pounds to soldiers' packs. They took an immediate dislike to its taste.

Then more problems arose: the cans would rust. Labels would fall off, leaving one to guess what each can held. The army came out with an improved C ration -- somewhat lighter -- in 1944, but it still had to fight off a lingering unsavory reputation.

Meanwhile, the Army set out to create a lighter field ration. What they got was even less appetizing, but better in combat situations. In 1942 a physiologist named Keys pioneered the K ration. Whether or not the K reflected Keys's name, we don't know. But the lemonade powder in the K ration was so acidic that it was reported to work better as a floor cleaner than as a drink. I don't recall ever having eaten a K ration myself.

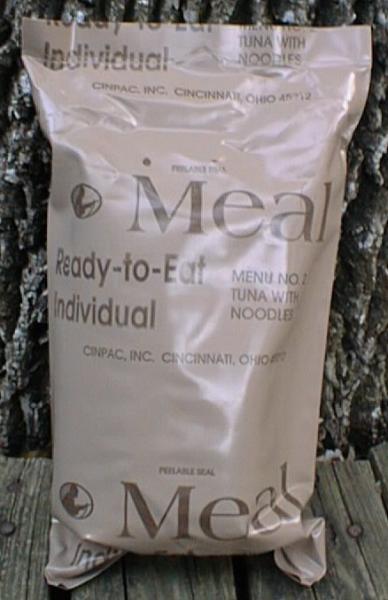

Today's combat ration is the MRE. That stands for Meal, Ready-to-Eat. MREs are highly processed, well-packaged food. Tin cans have given way to light-weight plastic. MREs offer 24 choices of menu including Chinese, Mexican, and Jamaican. They even have chemical heaters. Add water, and a reaction takes place in an outer sleeve making a warm meal of it. By all reports MREs are lighter, tastier, healthier, and far better all around than the old C ration. Still, when Desert Storm troops found themselves eating MREs for days on end, they renamed them Meals Rejected by Everyone.

Feeding an Army is a terrible challenge. Problems of weight and packaging are vastly magnified on a battlefield. Grocery stores supply food to kitchens: combat rations have to be ready for use in an open field. Cafeterias feed hundreds: armies feed thousands. It's no wonder that, when I was a soldier, we would sing the song,

Oh the coffee in the Army,

They say it's simply fine.

It's good for cuts and bruises,

And it tastes like iodine.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Moran, B., Dinner Goes to War: The Long Battle for Edible Combat Rations is Finally Being Won. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Summer 1998, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10-19.

There's a great deal of information about MREs on the web. Information on the now extinct C, D, and K rations is much harder to come by on the web.

For full size images click on the thumbnails above

A "No. 2 MRE" on the left and its contents on the right

(with my thanks to Jeff Mackey)