Fleming's Electric Valve

Today, an analogy changes our world. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The name Edison Effect was given to a phenomenon Edison observed in 1875, although it'd been reported two years earlier in England. Edison refined the idea in 1883, while he was trying to improve his new incandescent lamp. The effect is this: in a vacuum, electrons flow from a heated element -- like an incandescent lamp filament -- to a cooler metal plate.

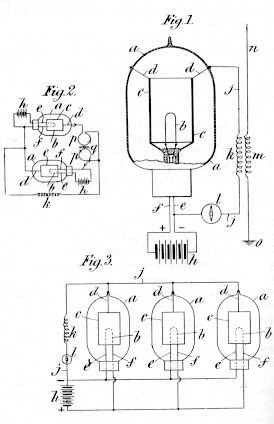

Edison saw no special value in the effect, but he applied for a patent anyway. Edison patented anything that might ever be of value. Today we call the effect by the more descriptive term thermionic emission. In any case, the magic of the effect is that electrons can flow only from the hot element to the cool plate, but not the other way. Put a hot and a cold plate in a vacuum and you have an electrical check valve just like check valves in water systems. Today we call a device that lets electricity flow only one way a diode. It was 1904 before anyone put the effect to use. Then the application had nothing to do with light bulbs.

Radio was in its infancy, and the English scientist John Ambrose Fleming was working for the British "Wireless Telegraphy" Company. Fleming faced the problem of converting a weak alternating current into a direct current that could actuate a meter or a telephone receiver. Luckily, he'd previously consulted for the Edison & Swan Electric Light Company of London. The connection suddenly clicked in his mind. He later wrote,

To my delight I ... found that we had, in this peculiar kind of electric lamp, a solution ...

Fleming realized that an Edison effect lamp would convert alternating current to a direct current because it let the electricity flow only one way. So he created the first vacuum tube. By now, vacuum tubes have largely been replaced with solid-state transistors; but they haven't vanished entirely. They still survive, in modified forms -- in things like television picture tubes and X-ray sources.

Fleming lived to the age of 95. He died just as WW-II was ending, and he remained an old-school conservative. Born before Darwin, he was anti-evolution to the end. Yet even his objection to Darwinism had its own creative turn. "The use of the word evolution to describe an automatic process is entirely unjustified," he wrote, turning the issue from science to semantics.

In an odd way, semantics marked Fleming's invention as well. He always used the term valve for his vacuum tube. In that he reminds us that true inventors take ideas out of context and fit them into new contexts. Fleming stirred so much together to give us the vacuum tube -- light bulbs, radio, and water supply systems.

But that's how invention works. Inventors turn bread-mold into penicillin, coal into electricity, and, at least figuratively, lead into gold, by refusing to keep any thought in its own container.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

MacGregor-Morris, J. T., The Inventor of the Valve. London: The Television Society, 1954.

I am grateful to Nancy Day, of the Linda Hall Library, for providing the MacGregor-Morris source.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 23.

J. A. Fleming's 1904 patent Drawing