The Prehistory of Motorcycles

Today, the motorcycle rides out of the Civil War. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The motorcycle can be an odd brain-teaser. It combines the instability of the bicycle with the power of an automobile. We usually credit the German car-builder Gottlieb Daimler with building the first motorcycle. In 1885 Daimler built a motor-powered bicycle but then added side wheels to stabilize it. What he really had was an embryonic automobile.

By 1885 the modern bicycle was about twenty years old -- the machine with two equal wheels and a chain-sprocket drive. By the time Daimler made his pseudo-motorcycle, bicycle people had realized how unnecessary his extra side wheels were.

So it should be no surprise that the idea of a motor drive arose right on the wheels of the first modern bicycle, seventeen years before Daimler. What is surprising is that the idea didn't catch on.

Writer Allan Girdler tells about Sylvester Roper, born in 1823 in New Hampshire. During the Civil War, Roper worked in the Springfield Armory, where his interest turned to steam power. In 1868, Roper built a steam-powered motorcycle.

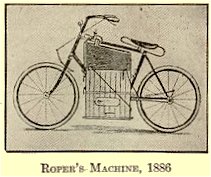

Roper's machine was remarkable by any standard. It looked a lot like the new bicycles, but with a small vertical steam boiler under the seat, which also held a small water tank. The boiler supplied two small pistons that powered a crank drive on the back wheel. Very neat and compact, and there was more: Roper controlled the steam throttle by twisting the bike's straight handlebar. Twist-grip control was later reinvented by the early pilot Glen Curtiss. It was invented, yet again, at the Indian Motorcycle Company.

Roper went on to build more motorcycles and several steam- powered automobiles. He probably built his first car during the Civil War. He was far ahead of his time with all his inventions. The Stanleys, who built Stanley Steamers, said they'd learned from Roper.

Roper reached the age of 73 in 1896. That June he showed up at a bicycle track near Harvard with a modified motorcycle. They clocked him at a remarkable forty miles an hour. Then the machine wobbled, and Roper fell off. He was dead when they found him. The autopsy showed he'd died, not from the fall, but of a heart attack.

It was another decade before the Indian Company began making commercial motorcycles. And we're tempted to see it all as terribly unfair. Roper didn't get credit for inventing the motorcycle or the steam automobile.

But that's not how it works. Driven inventors, the Ropers of this world, always precede the product-success stories. Since invention is an alien among us, we reject it and we wait for Daimlers, Stanleys, Fords, and Harleys to make commercial sense of invention.

And yet it is not just that the Ropers are the ones who finally sleep the sleep of the just. It's more than that. It is that they are the ones who, in the end -- have had all the fun.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Girdler, A., First Fired, First Forgotten. Cycle World, February 1998, pp. 62-70.

I am grateful to Keith Hollingsworth, UH Mechanical Engineering Department, for calling my attention to Roper's motorcycle. For more on Daimler's motorcycle, see Episode 921.

Roper's original 1869 motorcycle

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

From the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica

Two illustrations from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica showing early motor-powered vehicles. The four-wheeler on the right was built by Richard Trevithick, inventor of the first successful railroad, in 1802. On the right, an 1885 motor-powered tricycle.