Carriages

Today, let's ride a gig, or a hack, or a phaeton. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Never was I so struck by the erasure of an epoch in American life as I was the evening I recently spoke at the Carriage Museum in Stony Brook, New York. I had little idea what to expect when I entered. I hadn't known I was about to see one of the finest collections of horse-drawn vehicles in the world.

I'd hardly given a thought to horse-drawn transportation and now I faced beauty and variety far beyond anything I'd imagined. It made me wonder what a visitor from the 23rd century would think on his first visit to a museum of 20th century powered vehicles. What a shock all that variety of Mack Trucks, Duesenbergs, Fords, golf carts and fire trucks would be!

So it is with carriages. The array of carriages is newer than you might think. Riding alone on horseback couldn't give way to three and four wheeled vehicles until Europe began developing extensive road systems. The closed carriage probably came out of a Hungarian town whose name was spelled K-o-c-z and pronounced, coach. That was in the 15th century, and the name, coach, stuck.

A century later, vehicles had evolved leaf spring suspensions and better seating arrangements. Still, English carriage builders didn't form their first guild until 1677. By the 18th century, carriages were forcing the development of greatly improved roads. In 1815, MacAdam invented his bituminous macadamized road surface.

All this was sophisticated technology. We didn't begin serious carriage building this side of the Atlantic until shortly before the American Revolution. The first uniquely American rig was the pleasure wagon, a light basketlike vehicle. Next was the American buggy, the 19th century Model-T of personal transportation.

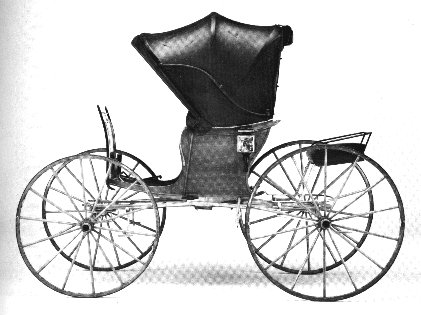

We also built closed coaches, but utility seems to've marked American building. I see the greatest beauty in the lightness and buoyancy of those modest buggies, shays, and phaetons. (A phaeton had a light convertible top over a front seat, with an open rumble seat behind.)

Oliver Wendell Holmes celebrated that delicacy in his poem about the The Wonderful 'One-Horse Shay', which was designed so perfectly that it lasted a hundred years and then fell into dust all at once. Holmes was a doctor, wishing the human body could work that way.

One of the notable 19th century buggy makers was the Studebaker company. But few other makers survived the transition to motor cars. The new engines were far more powerful than horses and they soon devalued the lightness and grace of the old carriages. As a child, I saw the last horse drawn vehicles on my city streets. They were, by then, shabby and worn.

And I didn't know, before I entered this museum, all the functional beauty that vanished in a blink during my parent's lives.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The Carriage Collection. Stony Brook, NY: The Museums at Stony Brook, 1986 (no author given.)

19th Century American Carriages: Their Manufacture, Decoration and Use. Stony Brook, NY: The Museums at Stony Brook, 1987 (no author given.)

The Carriage Museum. Stony Brook, NY: The Museums at Stony Brook, 1987 (no author given.)

I am grateful to Amanda Meyers and Bill Ayres, from The Museums at Stony Brook for their help with this episode. The correct name of this particular museum is "The Dorothy and Ward Melville Carriage House." Check out the informative website of Carriage Museum of the Long Island Museum.

A Buckboard Phaeton, after 1880

Image courtesy of the Carriage Collection, Stony Brook Museums

The end of an era: A Stanhope Buggy built by Studebaker

Image courtesy of the Carriage Collection, Stony Brook Museums