A Window on the Huguenots

Today, an old book and a new look at creativity and dissent. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The eaves of the Louvre in Paris are lined with statues of famous French artists and intellectuals. One is Denis Papin. Papin invented a steam engine at least two decades before the English did and seventy years before Watt brought steam power to maturity.

But Papin was a French Protestant -- a Huguenot. The Huguenots had coexisted with French Catholics for a century. Then, after a rapid buildup of anti-Protestant sentiment in the 1680s, Louis XIV expelled the Huguenots. He drove Papin and 400,000 others off into Germany, England, and Canada. Huguenots found their way to Massachusetts, NewYork, and South Carolina where their progeny included revolutionaries like Alexander Hamilton and Paul Revere. Christian Huygens, another early experimenter with steam, was also among the intellectuals forced out of France.

During his peripatetic life, Papin never did bring the steam engine to fruition. Practical power-producing engines had to wait another 20 years for a Devonshire blacksmith named Thomas Newcomen.

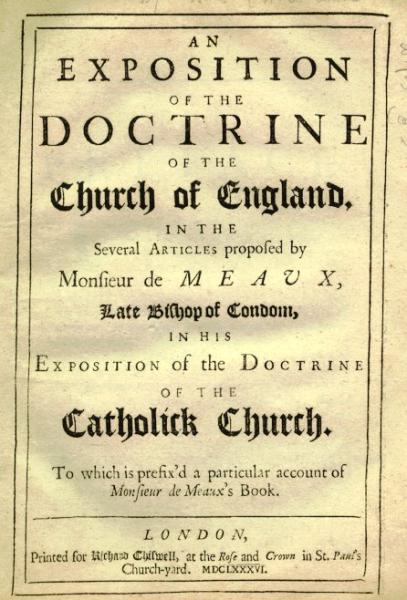

I recently caught up with an odd reflection of all that when I found a religious monograph from 1686 in a used bookstore. Such items have little market value, even when they're this old and in good condition. But a young cleric named William Wake wrote this book the year after Papin arrived in London. And Wake later went on to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

Wake had just returned from three years as chaplain to the English ambassador in France. He'd left along with the Huguenots, and here he tried to delineate the minor differences between Anglican and Catholic doctrine. He chided the French for hardening their position and turning from reason to assault.

Wake wrote fairly gently. He was still hoping for reconciliation. By the time he became archbishop, he was still struggling to reconcile religious differences -- this time with English dissidents. And it turns out that the steam-engine inventor Newcomen was one of those dissidents -- made from the same technological and spiritual stuff as Papin.

So religious nonconformity is woven through the history of steam power and the Industrial Revolution. This odd book is backdrop to that drama. As a young man, Wake objected to forces that were scattering people like Denis Papin and Christian Huygens.

But those two people scattered the way seeds scatter, and our modern industrial world sprang from those seeds. As an old man, Wake was still trying to make peace with dissent. But this time the refugees were shaking off English orthodoxy and forging a steam-powered economic revolution away from Anglican seats of power in London. I find this old book so appealing because Wake seems to have been one member of that establishment who valued dissent -- and the process which lies at the heart of all creative change.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Wake, W., An Exposition of the Doctrine of the Church of England in the Several Articles ... London: Printed for Richard Chiswell at the Rose and Crown in St. Paul's Church-yard. MDCLXXXVI. (The edition mentioned in the script above may be read in Special Collections and Archives, UH Library.)

Also useful were articles from the 1897 and 1911 editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica on the Huguenots, the Edict of Nantes, William Wake, Denis Papin, and Christian Huygens (who was somewhat older than Papin and who also did groundwork for the steam engine.)

I am grateful to Catherine Patterson, UH History Department, for her additional counsel.

Denis Papin as he appears on the eaves of the Louvre holding a steam piston in one hand

Photo by John Lienhard