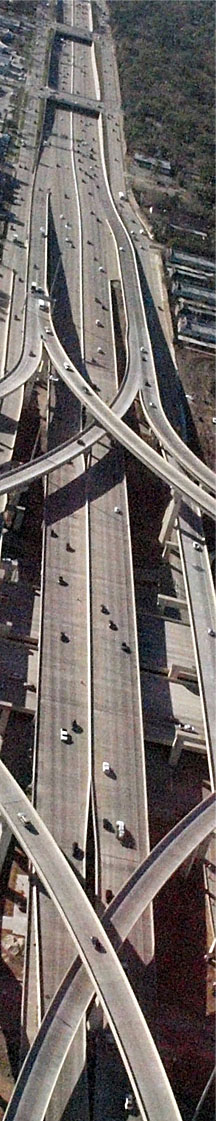

Houston, Texas

Cities are strange beings. They are alive, organic, and sentient. We are the cells and sinews of one such living breathing creature. It embodies our corporate self. It is you and me and all our neighbors — as well as the birds, bugs, and animals that live in symbiosis with us. And it is something else that we must not overlook. That something is our technological exoskeleton.

Our exoskeleton is the sum of houses, stores, sewers, orchestras, skyscrapers, dumps, factories, churches, roads, wires, and pipes. It is the sum of all the things we've made; it sustains us and it extends our minds and bodies. Our exoskeleton is huge, it is intimate, and we all share it.

The city is more still. Beyond ourselves and our vast exoskeleton, it also a living history. Consider this: A particular arrangement of living cells first saw the light of day in 1930 and it was named John Lienhard. The soft tissue cells in that cluster have died and been replaced countless times since then. Many are replaced more than once daily; only the skeletal cells last for years. As a result, nothing you see of this clutch of cells is left from 1930; very little remains even from the late 20th century.

The present me has almost nothing material in common with the 1930 me. Yet those cells, each of which had a very rudimentary form of intelligence, formed an ongoing system. They've died, but the system survives. It constantly changes, yet its identity persists because its cells are linked by their own history.

The city of Houston, Texas, was likewise founded in 1836. The oldest of its remaining architectural "cells" is probably the 1847 Kellum-Noble House. It still stands where it was built, in today's downtown, surrounded by skyscrapers of a wholly different era. And every animate being in Houston was born after that Kellum House.

The 1847 Kellum-Noble house

But a city's identity, like yours and mine, persists despite the ongoing replacement of its elements. The same individual factors that let me recognize classmates at my 60th high school reunion are those that let a city's unique personality outlive its parts. Our city thus becomes a very special context that frames and defines who we are. That's why it has its own personality. We wouldn't need posted signs to tell us whether we were in New York, Houston, or Los Angeles; each city has its own rhythm — its own voice.

The city was an invention that could be made only after the rise of agriculture, some 9000 years ago. Once we'd been wedded to planted crops, no longer hunter-gathering nomads, we settled in groups, near our fields. We joined one another in building granaries and creating means to protect them. We used our surplus food to feed artisans and technologists, poets and philosophers. Ever since then, the city, like all other living creatures, has been evolving. So we shall look at our cities, old and new, and ask how they've altered us as a living species. We'll look at the special circumstances that have given each its own face and its own unique place in history. And we'll arbitrarily begin this quest for the soul of the city in the Indus Valley, some 5000 years ago.

Freeway in Houston, Texas

Sources:

J. H. Lienhard, More Than a Sum of Parts. CITE: The Architecture + Design Review of Houston, Vol. 79, Summer 2009, pp. 42-45

See also Episode 2460

Images: downtown and freeway photographs by J.H. Lienhard. Kellum-Noble house image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.