particular copy of another Marcet book provides a virtual road map for tracing the complex symbiosis among the new fast presses and the creators of everyman's literature that she pioneered. It's a late edition of her Conversations on Natural Philosophy. This book was first published in London in 1819, at a time when natural philosophy included almost all science. It swept in astronomy, geography, biology, zoology – whatever an author fancied. In this book, Mrs. B, Emily, and Caroline talk about materials and motion, Newton's laws, hydraulics, heat, light, optics, and electricity.

particular copy of another Marcet book provides a virtual road map for tracing the complex symbiosis among the new fast presses and the creators of everyman's literature that she pioneered. It's a late edition of her Conversations on Natural Philosophy. This book was first published in London in 1819, at a time when natural philosophy included almost all science. It swept in astronomy, geography, biology, zoology – whatever an author fancied. In this book, Mrs. B, Emily, and Caroline talk about materials and motion, Newton's laws, hydraulics, heat, light, optics, and electricity.

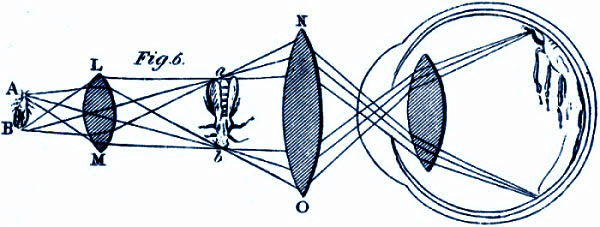

Marcet shows how one's eye sees a bug through a compound microscope

Fifteen years after Marcet first published this book, we find an 1834 American edition. As we read closely, we find ourselves tracing the entire story of the early 19th-century print revolution in microcosm. The book's condition can be described only as wretched. It's been used, stained, and worn down to the nub. In the front of the book is an ink-blotty signature: "Joseph L. Whittenburg's book May 13, 1838".

He used a poorly-cut quill pen that splayed erratically as he tried to write with it. Seventeen-year-old Whittenburg represents himself as a farmer whenever he shows up in subsequent census records. He was born in Missouri, and lived for some time in Alabama. He died in Texas in 1903 or 1905. Wherever he was when he got this book, he was still living in a remote and harsh land. He signed the book several times more – in 1846, 1848, and 1850. Was he making note of the times he went back to refresh his understanding, or just reasserting his ownership? We do not know, for he left even fewer tracks in the record of history than Mary Anne Howley did.

He used a poorly-cut quill pen that splayed erratically as he tried to write with it. Seventeen-year-old Whittenburg represents himself as a farmer whenever he shows up in subsequent census records. He was born in Missouri, and lived for some time in Alabama. He died in Texas in 1903 or 1905. Wherever he was when he got this book, he was still living in a remote and harsh land. He signed the book several times more – in 1846, 1848, and 1850. Was he making note of the times he went back to refresh his understanding, or just reasserting his ownership? We do not know, for he left even fewer tracks in the record of history than Mary Anne Howley did.

The book itself is a far cry from Howley's carefully hand-finished chemistry text. She had to cut the folded pages of her book apart before she could read it. The cotton rag paper of her book was still clean and supple.

Whittenburg's book, on the other hand, is completely factory-made on a roller press. No more need to cut the pages apart, no more book-bindery finishing. And, as cheap books like his poured forth, there were no longer enough cotton rags to supply paper makers. Wood pulp paper wouldn't be invented for decades, so paper makers had to mix other plant fibers in with cotton and add chemicals to digest them. Now the pages are discolored in various ways, depending upon which batch of paper was used.

This is a new world – one in which one no longer had to be upper middle class to afford a book. Reading has been democratized as never before. Our diffuse agrarian American population, with schools few and far between, was determined to to be learned, even if it was hard put to be educated. I sing the praises of these shabby factory-made books, for they were now forming us into a people of enormous energy and confidence.

See e.g., J. H. Marcet, Conversations on Natural Philosophy. (Boston: Lincoln, Edmonds & Co., 1834). This (Whittenburg's copy) is one of many later editions of Marcet's natural philosophy book. It bears the name of J. L. Blake on its title page and is sometimes catalogued under his name.