The 19th-century obsession with the delight of energy was remarkable. The century gave us a most extraordinary technological leap forward. And that delight in energy was wreathed in steam. The steam engine has to be the defining icon of that era.

The world of 1800 was one without powered vehicles, without steel construction — without typewriters, fast presses, airships, photography, electric lights — without the elements of modern medicine, and certainly without programmable computation. Yet, by 1900, we had all that. Then everything changed.

The 20th century added radio, electronics, TV, airplanes ... quantum mechanics and relativity theory. Not just technology, but science itself, turned into something radically new. The 20th century arrived with a huge systemic shock.

The Victorians had looked upon all they'd done with unsurprising hubris. They thought their machines had reached a pinnacle. They knew their technology could be articulated in new ways. But they expected only to rearrange and improve what they already had. The Victorians had no clue that the modern era would turn their world on its ear. Well, few of them did.

Henry Adams visited the 1900 Paris Exhibition. There he found some serious hints as to what was about to come. He wrote: "[I found myself] lying in the Gallery of Machines — my historical neck broken by the sudden irruption of forces totally new."

Of course, Adams stood on the doorstep of that new century. He was able to peek over the threshold. So let's, instead, back up and think about Adam's contemporary, Jules Verne.

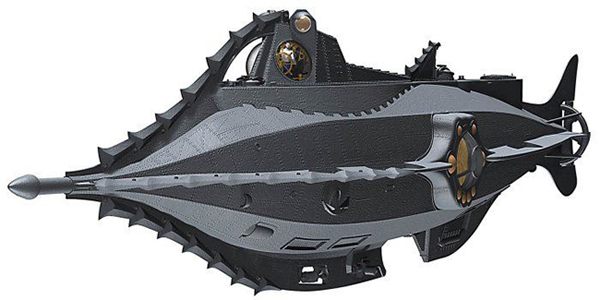

Verne saw Victorian machinery being developed into great submarines and dirigibles — trips to the moon and to the center of the earth. His books are now part of a literary genre that we call steampunk. Steampunk is a fusion of science fiction with alternate history. It expands upon 19th century technology without admitting any later science. People coined the term in the late 1980s and there followed a new spate of movies and books celebrating that old world of steam.

Jules Verne's Nautilus Submarine as envisioned in the 1954 movie, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. (Pure steampunk, long before the word was invented.)

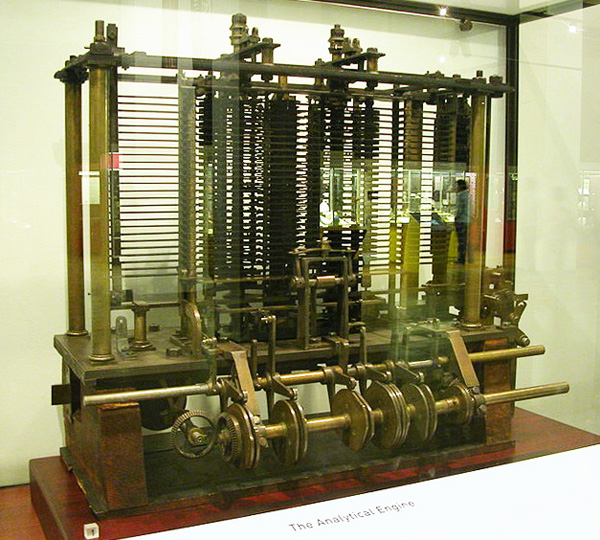

Remember The Golden Compass or The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen? Perhaps you've read Gibson and Sterling's 1991 book, The Difference Engine. It gave us a computerized Victorian world. You see, mathematician Charles Babbage had, in 1837, proposed a kind of programmable calculating machine. The idea was to feed it punched cards and turn a crank. Its complex gears would then do pretty much what a modern programmable computer does. Babbage never got the thing to work. The gearing was too complex and it would take too much power to drive it.

Still, a steam powered computer certainly would eventually have been within the scope of Victorian technology. In fact, steampunk aficionados continue to complete such machines in our own times.

Model of a portion of Babbage's Analytical Engine, London's Science Museum [Photo by Bruno Barral, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]

Steam really had been a magic elixir pulsing through the Victorian age. So the imagined high-tech citizens of the steampunk world do calculations with steam-driven Analytical Engines. Steam engines drive fast-moving steampunk airships. Armies might have shock troops flying over enemy lines with backpack balloons. An alternate history, shaped without the airplane, might yield a very different map of Europe. (We can actually order such maps online).

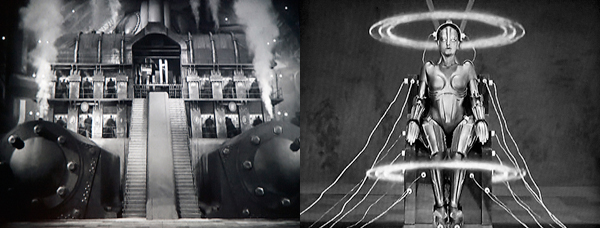

The steampunk idea has evolved ever since the 19th century. Not long after Jules Verne, the 1927 movie Metropolis showed a dark steam-driven underground hell, serving idyllic Victorian comforts in the sunshine above.

Images from Fritz Lange's movie Metropolis: Left, the steam-powered, Hellish underground. Right, the mad scientist's creation. [TV screen photos]

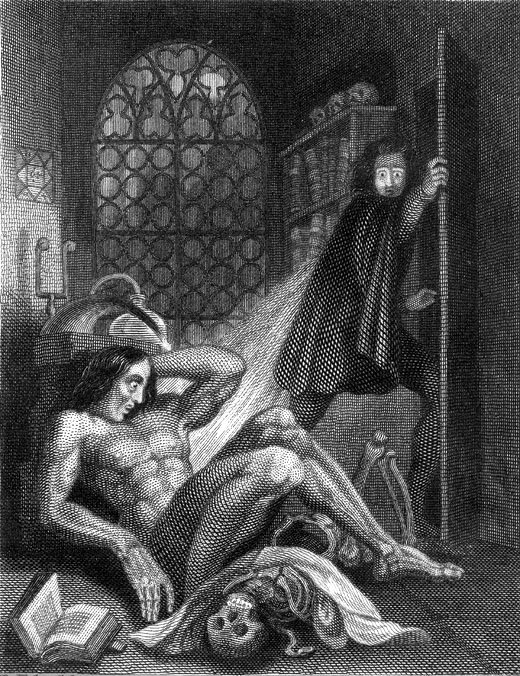

Even before Verne, Mary Shelley hinted at the essence of the idea in Frankenstein. She wrote, "I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, ... stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Her unexplained engine, of course, had to've been powered by steam."

Frontispiece of the 1831 edition of Shelley's Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus.

Any science fiction does this — envisions futures based on what's already known. It can't predict anything really new. It can suggest only futures based on what is known. Jules Verne did fairly well with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea because submarines already existed. But his Trip to the Moon imagined technology just as silly as centuries of moon-voyage sci-fi before him.

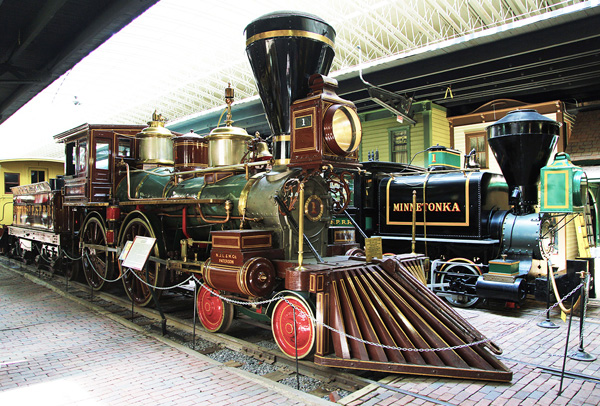

... and what could be more beautifully Steampunk than the Iconic 4-4-0 locomotive, called the "American Type" locomotive [Duluth, MI, Depot Museum, photo by J. H. Lienhard]

Steampunk is smarter than that. It says, "Let's embrace nostalgia. Let's predict a fictitious future where we consciously disallow new knowledge." Steampunk goes back to that glorious era of steam and rivets and asks what might've come of it if engineers and scientists had not derailed it. What if we hadn't scrambled things with our newfangled transistors, airplanes, and radio waves?

The huge Quincy Mine Cable Hoist (Hancock, MI) driven by four steam cylinders is pure Steampunk in conception, although it was built in 1920. [Photo by J. H. Lienhard]

Sources

Adams, H., The Education of Henry Adams. (New York: The Heritage Press, 1918 — or one of the many subsequent printings) See especially Chapter 25 and, to some extent, the subsequent chapters.

See the Wikipedia, the Steampunk Magazine, and Steampunk Workshop sites for more on steampunk.

An archetypical novel of the late 20th century steampunk revival is W. Gibson and B. Sterling, The Difference Engine. (Bantam Spectra, 1991). The book cover above is for the more recent book: K. McIntyre, An Airship Named Desire. (Hazardous Press, 2012).

The Mary Shelley quote is from the Author’s introduction to the 1818 edition of Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus.

See Engines Episode 1537 for more on very early science fiction about travel to the moon.

For an account of the texture of the huge shift from the 19th to the 20th century, see: J. H. Lienhard, Inventing Modern: Growing up with X-Rays, Skyscrapers and Tailfins. (New York, Oxford University Press): Chapters 1, 2, & 3.

For a history of the rise of the 19th century world portrayed by steampunk, see: J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines. (New York, Oxford University Press): Chapters 4 through 8.