Moving Obelisks

Today, the ancients throw down a challenge, and we're hard-pressed to meet it. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The ancient Egyptians surprise us again and again with their scale of building. Take the obelisk, a long tapered monolith topped with a small pyramidal cap and inscribed with hieroglyphs honoring the gods and telling of kings who lived in its shadow.

The Washington Monument is shaped like an obelisk, but it has stone facing on a steel skeleton. A true obelisk is a single piece of stone. From 2300 to 1300 BC, the Egyptians cut and erected dozens of monster obelisks. Some were over 100 feet high and reached weights of 500 tons -- as much as a small cargo ship.

Yet, after they were quarried, obelisks had to be moved and lifted into position. The Egyptians did that over and over again; later generations seldom tried. Bern Dibner tells how a few Roman Caesars moved big obelisks. They even hauled them across the Mediterranean. They carried a 370-ton obelisk in a ship powered by 300 oarsmen. Much later, in 1586, an Italian engineer made modern history by relocating that same obelisk to the square in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

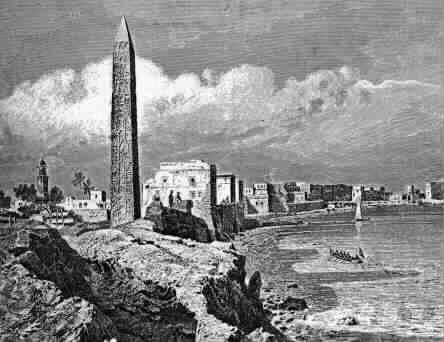

After the English took Egypt from Napoleon, they took an interest in two 200-ton obelisks that'd first been erected at Heliopolis 3500 years ago. Caesar Augustus had them moved to Alexandria just before the birth of Christ. In 1819 Egypt told England they could have one. It took 58 years and the development of ocean steamers before England could claim it. They finally built a huge cylindrical barge ship called the Cleopatra.

It took weeks to load the obelisk into the Cleopatra. Then the steamer Olga towed it away. When a storm rose in the Bay of Biscay, the Cleopatra began heeling over. Six seamen drowned trying to set it right. The Olga's captain thought Cleopatra was lost. He cut her loose and fled. Another ship found the floating obelisk and brought that eerie prize to England for salvage. Today, it stands on the Thames River embankment.

William Vanderbilt hired Civil War veteran Henry Gorringe to move the companion obelisk from Egypt to New York. Gorringe took a large ship to Alexandria and put it in dry dock there. He cut a huge hole in the hull near the bow and loaded the obelisk into it. It took him a year and a 50-percent cost overrun to wrestle it into place in Central Park. And there it stands today.

But the Romans did all that without steam power, and the Egyptians before them carved and moved those stones without even gears or power screws. However, the ancient Egyptians did have something beyond raw muscle. They used the three things that underlie any great technology to move those stones: cooperation, inventive genius -- and a powerful will to succeed.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Dibner, B., Moving the Obelisks, Norwalk, CT, Burndy Library, 1991.

Image courtesy of the Burndy Library, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology

Obelisk moved to Alexandria by the Romans (from Moving the Obelisks)

Image courtesy of the Burndy Library, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology

Loading an obelisk through a hole in the steamship Dessoug (from Moving the Obelisks)

Image courtesy of the Burndy Library, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology

The pontoon ship Cleopatra being abandoned by the ship Olga (from Moving the Obelisks)

Image courtesy of the Burndy Library, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology

Obelisk mover Henry H. Gorringe (from Moving the Obelisks)

Photo by John Lienhard

And this Egyptian obelisk came to rest in Paris