Ullage in a Pen

Today, let's ask if you can recognize ullage when you see it. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It was a fine seminar in Galveston about how scientists visualize nature -- all the ways we see before we understand.

When a great British art historian rose to talk about 18th-century anatomical illustration, he by began noting that our historic meeting building was an artistic mish-mosh. Design, he said, is often filled with frivolous trim and mixed statements.

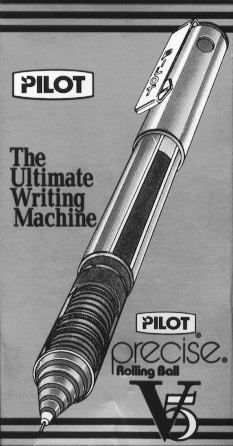

He held up one of our meeting pens. "Look at the clear plastic nose with the concentric disks in it," he said, "Someone wanted to evoke spaceships, and they've created design nonsense."

I've carried the pen for two months now and studied the way ink moves through those disks. The pen writes beautifully in any orientation. There had to be more than met the eye in that design. I finally called the Pilot Pen Corporation to ask about those disks. A representative told me how they worked:

The trick is to keep just the right amount of ink in contact with the wick that feeds the delicate roller ball tip. The discs are baffles that balance the forces of surface tension against air flow resistance. Regardless of the angle, just the right amount of ink stays in contact with the wick.

It turns out that the historian was right on target with his idea that the pen evokes spaceships. It really does. You see, NASA rockets carry liquid fuels, water for the crew, coolants -- liquid that has to be moved about with no help from gravity.

That means containers need complex baffles that let surface tension position the liquids. NASA uses the old English word ullage to describe that process. Ullage once meant the empty space in a barrel of wine. Now we use it for the empty space in a barrel of liquid oxygen.

Of course, it also applies to the empty space in the barrel of a pen. The irony is that forms of this elegant technology were hidden in fine fountain pens as long as a century ago.

So the art historian went on to show us majestic prints from great, but little known, books on anatomy --all kinds of original material. We saw the astonishing skill with which visionaries saw into, and then represented, the human body 300 years ago.

But in the end, that elegant pen puts the visual greatness of our medical forbears into perspective. Technology is vision, and vision is subtle. Our 19th-century meeting building was an adaptation to needs and constraints that aren't apparent today. That pen point turns out to be a virtual laboratory in complex fluid movement. And we're reminded:

Far more design genius is all around us -- at the tips of our fingers -- than the best of us know how to see.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The conference I refer to here was called Visualizing Science: Representations in Science and Technology. It was arranged by the Institute for Medical Humanities at the University of Texas Medical Branch, and it took place at the Tremont Hotel in Galveston from April 28 to May 1, 1994.

I am especially grateful to John Ferrara, Customer Service Manager of Pilot Corporation of America, 60 Commerce Drive, Trumbull, CT 06611, for his explanation of ullage in the Pilot Point "Precise" roller ball pen. Kate Krause, UH Library, located the Pilot Corporation sources for me.

Image courtesy of Pilot Corporation