Why the Wrights Flew

Today, an unfamiliar side of Wilbur and Orville Wright. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Lots of people had tried to create the airplane by 1903. Historian Tom Crouch asks why the Wrights succeeded where others failed. Wilbur once said that, if time were turned back and they did it all over, it was unlikely things would come out the same.

That was an oddly accurate statement. They had to put so many pieces together to make an airplane that really flew. And yet, we wonder, was their success really just chance?

Their father, Milton Wright, was a combative bishop of the United Brethren Church. His uncompromising doctrinal fights split the Church in two. While he waged religious war outside, he made his home into a fortified oasis of love and peace. His seven children inherited his rigidity and sense of family isolation. All obeyed a stern code of work and ethics.

In 1889, when Wilbur was 20 and Orville 17, they set up a printing business under the name, "The Wright Brothers." They did that work for six years, redesigning commercial presses and adding the famed bicycle sales and repair service along the way.

Later in life, they told people that their interest in flight began when they were children and their father gave them a toy helicopter. But it was in their mid-20s that they began reading the work of Lilienthal, Chanute, and Langley on flight.

For seven years they studied with relentless thoroughness. They built their own wind tunnel. They did countless preliminary glider flights. They designed their own airplane engine.

They also argued furiously with each other. Their mechanic told how the brothers would switch positions in the middle of a shouting match without losing a beat. Wilbur once said, "I love to scrap with Orv. He's such a good scrapper." Crouch looks at the two and says, "The whole was greater than the parts."

Beyond their ferocity of purpose, they also had an uncanny ability to abstract problems spatially. We credit them with inventing the powered airplane. But others had already left ground only to crash. The Wrights didn't just power their way into the sky. They figured out how to stay aloft.

They looked at birds. Birds control their own unstable flight in three dimensions. Controlling an unstable bicycle in only two dimensions is complex enough. They extended that into 3-D and figured out how to do it using aerodynamic forces.

Wilbur was right when he said it might come out differently if time were turned back. But their synergy, based on abstract thinking and practical sense, coupled with a terrifying passion and intensity, would've left Earth changed in some way. Of that I have no doubt.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Crouch, T.D., Why Wilbur and Orville? Some Thoughts on the Wright Brothers and the Process of Invention, Inventive Minds, (R.J. Weber and D.N. Perkins, eds.) New York: Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 80-92. (I am grateful to Peter C. Maffitt for suggesting, and providing, this source.)

Howard, F., Wilbur and Orville: A Biography of the Wright Brothers. New York: Ballantine Books, 1988.

From The Men Who Learned to Fly, 1908

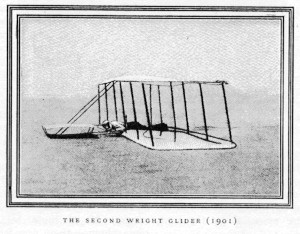

The Second Wright glider aloft in 1901