Of Power and Gold

Today, let's talk about power and the gold rush. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

They say gold is power. But then, in 1776, Matthew Boulton made a related remark to James Boswell. When Boswell visited the Boulton-Watt factory, Boulton said to him, "We sell here, Sir, what all the world desires to have -- Power."

In 1848, 72 years later, at Sutter's Fort in California, my great-grandfather Heinrich was putting in a vegetable garden for Sutter. Everything was still labor-intensive. Watt's power-producing engines had yet to reach this remote outback.

Sutter had been acting strangely for two weeks. One evening he showed Heinrich and some other friends a small bag of yellow metal grains. Could it be gold? Heinrich described a malleability test and suggested they try it at the blacksmith's shop. They cleaned a spoon, heated it, and put a metal grain in it. When they hammered the hot metal, it spread out smoothly as gold does and its imitators do not. Sutter had indeed located gold.

The story leaked out, and the rest is history. But great-grandpa Heinrich was bothered. Who had really found the gold, and where? Everyone was making claims -- Sutter included.

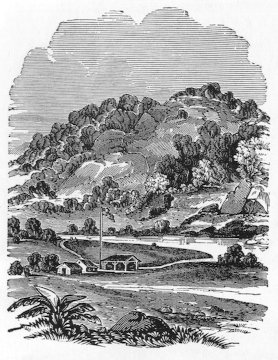

Heinrich finally tracked down the source. One James Marshall had been trying to build a grain mill, 50 miles back in the mountains. Marshall was testing the water-diversion system he'd dug to supply his undershot water wheel. As water sluiced through the fresh-cut dirt it had exposed the gold nuggets.

We all know about the discovery of gold, but what of Marshall's water wheel? Marshall had made a deal with Sutter to build two mills. He'd managed to finish a sawmill down-river from the fort. Now he was having trouble with the grain mill. Neither mill appears to've been very successful. The other pioneers called them, "Sutter's Follies."

Once there was gold, it was a different story. Now steam-powered ships turned up in San Francisco Bay with would-be gold miners. The new Pelton Wheel water turbines were soon powering California's mines. One man even tried to build a steam-powered dirigible to carry passengers from New York to the gold fields.

Many of the first settlers were European. They were trying, with only spotty success, to recreate the simple technologies of medieval Europe. Now, even before the spring snows of 1849 had melted, power followed gold in shaping the American West.

Today the gold is gone, while power production has reached levels that would've been unimaginable in 1849. And what of great-grandpa Heinrich? Well, he turned his back on power and gold. He retired to Nauvoo, Illinois, and spent his own small fortune in gold. He transmuted it into the finest rose garden in town.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lienhard, H., A Pioneer at Sutter's Fort. 1846-1850: The Adventures of Heinrich Lienhard (Translated, edited, and Annotated by M.E. Wilbur). Los Angeles: the Calafia Society, 1941.

Herron, M., The Rush is on to Find New Gold in Falling Water. Smithsonian, Dec. 1982, pp. 87-97.

Drawing of Sutter's Mill from the 1851 Harper's Magazine

Johann Heinrich Lienhard -- not long after his time with Sutter