A Need for Danger

Today, let us frighten ourselves -- just a little. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The modern amusement park evolved for centuries. Historian Judith Adams traces it to London's Bartholomew Fair -- a ten-day trade fair that ran annually for 722 years, from 1133 until 1855. Ben Jonson's play Bartholomew Fair, written in 1615, told about exotica, jugglers, monsters and marvels -- with pickpockets, pimps, and con artists swirling through it all.

We finally harnessed that kinetic excitement -- that elixir of danger -- only a century ago. By 1893, three new technologies of physical elation had entered the fair and changed it. They were the carousel, the roller coaster, and the Ferris wheel.

First, the carousel: It was the grandchild of an old Turkish jousting game. In the European version mounted players, dressed like knights, tried to run their lances through brass rings.

Then the steed became a wooden horse moving on a spoke, powered by a mule. Steam engines eventually replaced mules. In 1907 we added a gallop mechanism. Finally children bobbed around that magic circle on wooden horses to the music of a great calliope.

The ancestor of the roller coaster came out of 17th-century Russia -- a 70-foot snow-packed slide. You rode down it in a tiny two-man sled, like a luge in today's winter Olympic Games.

Parisians created a wheeled version in 1804. When it had broken enough bones, they began inventing safety features. But the biggest drawback remained. You had to haul your cart to the top before you could ride it down.

The American version came out in 1878. It had wavy side-by- side tracks running downhill in opposite directions. On each end, cranes hoisted carts back up the starting towers. The first one was built at Coney Island. So was the first fully evolved roller coaster, the famous Cyclone ride, built in 1927.

The last great ride had no prior history. Ferris simply sat down and dreamt it up for the 1893 Chicago Columbia Exposition. The first Ferris wheel was the grandest of them all, with a 264-foot diameter. It was three times larger than any since.

The Chicago Fair was to be a triumph of graceful urban design. They called it The White City and relegated the seamier side to a strip of land midway between the fair grounds and nearby Washington Park. That's where the rides and concessions went. That's where Ferris's great wheel stood and dominated the fair. That's how the word midway joined our vocabulary.

I live a mile from the spawn of all this: Houston's AstroWorld. Children bus in to ride those great looping gravity violators. They come to be charmed by motion and speed and to satisfy the still-terrible need for an illusion of danger.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Adams, J.A., The American Amusement Park Industry: A History of Technology and Thrills, Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991.

Applebaum, S., The Chicago World's Fair of 1893: A Photographic Record, New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1980.

I am grateful to Margaret Culbertson, UH Art and Architecture Library, for suggesting the topic and drawing my attention to the Adams source.

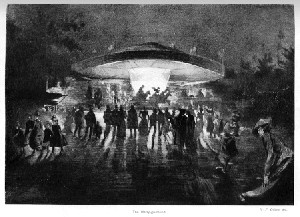

From the October, 1896, Scribner's Magazine

Image of a carousel from 1896. Perhaps it is no coincidence that it looks to us like a flying saucer landing on earth!