Lighthouses

Today, we say goodbye to lighthouses and cabooses. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Our railways are caught in a funny debate these days. The caboose is a kind of moving observation tower -- a way of seeing over and beyond a railway train. Electronic safety systems are making them obsolete, but cabooses are so much a part of the romance of railroading that no one wants to give them up. And that's how it is with lighthouses, too. Lighthouses and cabooses are woven into the romance of the rails and of the sea.

Lighthouses are used at night to mark any danger to shipping -- sea-crossings, rocks, major landfalls. The distance from the light to the horizon depends on how high the lamp is, so height is important. A 15-foot light can be seen for 4½ miles. A 120-foot light is visible over 12 miles away, and so forth.

That's why the Pharos at Alexandria was so big. One of the seven wonders of the ancient world, it held a huge bonfire 400 feet in the air. And, like it, lighthouses down through centuries were usually tall masonry towers mounted on shore -- maybe on shoreline cliffs -- burning wood or olive oil and, later, coal or candles. It was a pretty static technology. Rotating beams weren't invented until 1611. Reflectors weren't added until 1763. The first lens was introduced less than 200 years ago.

Lighthouse construction began to move again in 1698, when the English had to warn ships away from the Eddystone rocks, 14 miles southwest of Plymouth. You've probably heard the old folk song:

Oh, me father was the keeper of the Eddystone Light,

And he slept with a mermaid one fine night.

And from this union there came three,

A porpoise and a porgy -- and the other was me.

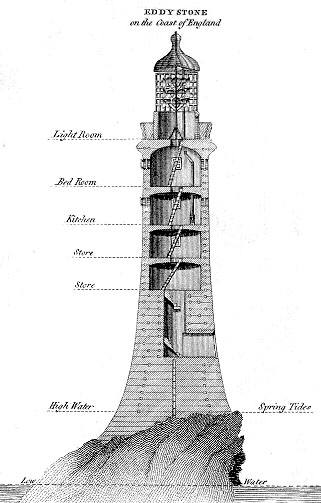

Well, building the Eddystone light was a terrible job. It had to be erected right at sea level, where it was hammered by waves. The first one, made of wood, lasted five years. The next, made of wood and iron, burned down after 47 years. The third, made in 1759 with a new kind of interlocking stone construction, stood. It wasn't replaced until 1881, and that Eddystone light is still with us.

But now radar, and sonar, and electronic buoys are putting an end to the lighthouse. We'll have to live in a world without cabooses on trains -- and without those beautiful storm-beaten minarets to call the weary sailor home.

The siren attraction of the lighthouse, like other technology past -- and, I suppose, like much technology yet to come -- is that good technology is contrived to fulfill human need. That's why it satisfies more than function. It expresses what's inside us. Good technology has symbolic as well as functional power. And that's why we're so loath to say goodbye to it.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This episode has been revised as Episode 1523.

(From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia)

The Eddystone Light designed by John Smeaton