Lawn Mowers

Today, an odd story about an invisible technology. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I'll bet you've never thought about the invention of lawn mowers. I hadn't either until I read an article on lawns by Margaret Culbertson. Our homes, golf courses, and institutions sit on thousands of square miles of close-cut grass. We clearly haven't had all those lawns any longer than we've had means for mowing them. Lawns never would've become such an American institution without lawn mowers.

So I went looking for the history of lawn mowers. What I found was a surprise. Almost nothing has been written about this machine that takes up such a huge part of our lives.

Lawns themselves took form in the 1700s. The French formal garden was a closed space with carefully tended grassy patches. When the British got their hands on that idea, they changed it radically. British estates had lawns that opened into nature. A lawn flowed away from a house, out into the surrounding woods.

To do that, the English invented the sunken fence -- a trench lined on one side with a vertical stone wall. It kept animals in but it was nearly invisible. It created the illusion that the house was simply part of nature around it.

Jefferson studied those English lawns. Then he built the idea into Monticello and the University of Virginia. We had the space we needed for lawns in America, but tending them was a labor. Grazing animals did some mowing. The rest had to be done with a sickle or a scythe.

In 1830 an English inventor, Edwin Budding, created the first lawn mower -- much like the hand-pushed mower you may've once used. Do you remember the old rotating helical blades?

The lawn mower caught on fast in America. Yet history has had very little to say about that key invention. In 1874 Beeton's Dictionary of Gardening already wrote it off as "too well-known to need description."

I earned my allowance in 1940 pushing a mower and trimming the lawn with a sickle. That's the year Leonard Goodall invented the rotary power mower and transformed lawn-mowing utterly.

Today we burn a half billion gallons of gas a year powering rotary mowers. We pour tens of thousands of tons of chemicals on our lawns. Lawns reflect a 200-year-old Romantic dream of fusing ourselves with nature. Yet that very dream now poses a major threat to the nature it so lovingly celebrates.

What a crowning irony! We so want the loveliness of nature that we put nature under assault to have it. We lay ourselves open to that sort of thing when we take our technologies for granted -- when we let them slip into invisibility.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Culbertson, M., The Lawn Goodbye, Cite, (Incomplete citation -- approximately Vol. 30 or 31, 1995.) Margaret Culbertson, UH Art and Architecture Librarian, also directed me to the source material, below.

Bormann, F.H., Balmori, D., and Geballe, G.T., Redesigning the American Lawn. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press, 1993.

Scott, F.J., The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds of Small Extent. New York: Appleton & Co., 1870.

Jackson, K.T., Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Goodall, L.E., the Rotary Power Mower and Its Inventor: Leonard B. Goodall. Missouri Historical Review. Vol 86, No. 3, 1992, pp. 248-264.

Geelhoed, B.E., Business and the American Family: A Local View. The Indiana Social Studies Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1980 pp. 58-67.

An original Budding lawn mower, London Science Museum, (Photo by John Lienhard)

View of the new lawn mowers in the December, 1896, Scribner's Magazine

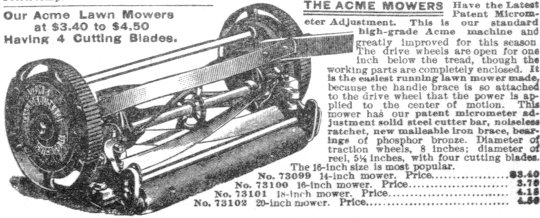

A lawn mower in the 1900 Sears Roebuck catalog