Locks

Today, let's talk about an oddly static technology. Let's talk about locks. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A zealous Lock-Smith dyed of late,

And did arrive at heaven gate,

He stood without and would not knocke,

Because he meant to picke the locke.

This bit of doggerel is, maybe, 400 years old. It says a lot about locks and the way we relate to them. Ask most people what a lock means to them and they'll tell you, "Security." Yet which of us wants to own a lock that can't be picked, in a pinch?

The locksmith in the poem craves the reward of having cracked the very vault of Heaven. And we're reminded that locks are also metaphors for human ingenuity. After we think of security, our mind leaps next to the puzzle of opening the lock.

Egypt made the first locks 4000 years ago. They used wood. They also used a system of pins moved by a key -- not all that different from modern locks. For four millennia, locks have been less a work of raw invention than of endless innovation.

The Greeks made metal pin locks, but they also challenged human ingenuity with another system entirely. Do you remember Alexander the Great cutting the Gordian knot? Well, many Greeks devised knots that only they could tie. Then they simply lashed their doors shut. Of course Alexander showed what any home-owner knows today. The locks on our doors only slow criminals down. They seldom keep a really determined thief out.

Medieval locks were wonderfully ornate on the outside, but they stayed fairly simple on the inside -- more status symbols for the wealthy than solid protection. The big shift in lock-making came after 1800. Once we began manufacturing with interchangeable parts, we took lock-making away from locksmiths and gave it to factories. Now anyone could afford a lock.

The people who created the lock design that took full advantage of the new system of manufacturing were Linus Yale, Sr. and Linus Yale, Jr. By 1860 they'd perfected the convenient pin-cylinder lock. Soon after that, a would-be poet could write,

You gave me the key to your heart, my love;

Then why do you make me knock?

"Oh, that was yesterday; Saints above,

Last night I changed the lock!"

Of course the Yale lock, secure as it is, can be picked once you know how. Even so, the most important developments in mechanical lock design in recent years are still variants on the Yale lock.

Now we threaten our 400-year-old lock metaphor with entirely new devices. We've invented electric locks that we key with memorized numbers -- or our palm print. The key question (pun intended) is, "Will the old mechanical lock outlast our generation?" It isn't just a simple device that's under assault. It is, in fact, one of our most powerful mechanical icons.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Ashley, S., Under Lock and Key. Mechanical Engineering, August, 1993, pp. 62-67.

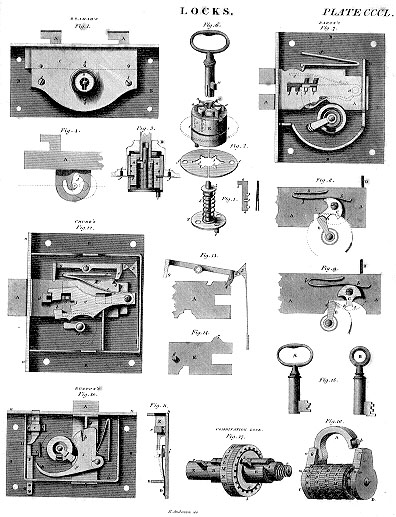

From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia

A variety of typical early 19th-century locks