Peter Cooper

Today, a millionaire who believed that wealth doesn't belong to the rich. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

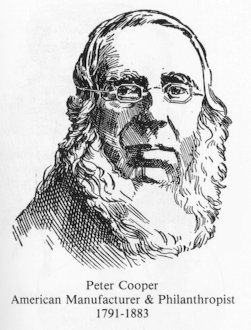

Few great 19th-century builders of America are as compelling as Peter Cooper. Cooper, born in 1791 in New York City, was a reckless kid, scarred by many accidents. He went on to become a great American inventor, a creative social reformer, and a wealthy egalitarian.

In his teens, apprenticed to a coach-maker, Cooper invented a machine for shaping wheel hubs. It was still in use when he died. Next he cooked up a complex scheme for getting power out of ocean tides. He built a model and showed it to Robert Fulton. Fulton gave Cooper no response at all -- only stony silence.

That event carved another scar into Cooper. He kept the model all his life. Why? Was it a dangling hope? Maybe it was his unhealed wound. We do not know.

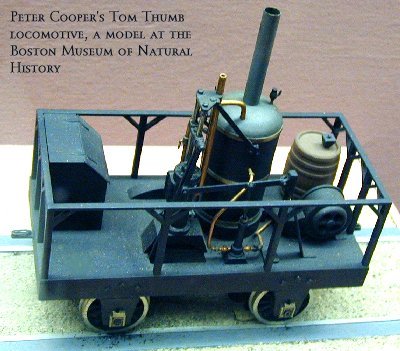

But he came away determined to invent. He patented a musical cradle, a process for making salt, a rotary steam engine. In 1825 he built America's first steam locomotive, the Tom Thumb.

Meanwhile, he acquired a glue factory. He built an iron mill. He grew rich. Yet Peter Cooper was not just another rapacious 19th-century industrialist. He was fueled by idealism.

He was a passionate abolitionist and a strong Lincoln supporter. He made a remarkable suggestion for averting civil war. He proposed that the North should simply buy all the slaves and free them. If buying off four million slaves sounds crazy -- well, compare it with four billion dollars and half a million lives lost in that war. Then it gains a bit in sanity.

Cooper had a flair for far-out, far-seeing projects. He was an important backer of the trans-Atlantic telegraph cable. He helped bring Bessemer steelmaking to America.

But the invention that captures my fancy was New York's Cooper Union. Why Union? Because the school was meant to unite science and art. More remarkably, it carried out Cooper's belief that "education be as free as water and air." It's always been small and tuition-free. If you have the talent to attend, you're awarded a scholarship.

Cooper meant his college to educate women as well as men. He meant it to serve the disadvantaged. Cooper himself had only one year of schooling. He was barely literate. In fact, his spelling was just as inventive as his machines and his politics.

In the end, one of his greatest contributions lay up on the third floor of Cooper Union. It was a public reading room. People poured into it from all over town. You see, right along with free education, Cooper helped shape another very new, and uniquely American, institution. That was the public library.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Mack, E.C., Peter Cooper: Citizen of New York New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1949.

Nevins, A., Abram S. Hewitt, With Some Account of Peter Cooper. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1935. (Hewitt was Cooper's son-in-law, and inventor and craftsman in his own right, and long-time associate of Cooper.)

Dunn, G., Peter Cooper (1791-1883) -- A Mechanic of New York. New York: The Newcomen Society in North America, 1949.

Gurko, M., The Lives and Times of Peter Cooper. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1959.

Too bad I didn't have time to talk about Cooper's ill-fated run at the Presidency! When he was 85, he ran on the Greenback ticket against Rutherford B. Hayes. It was not one of the great 3rd party efforts. He was a very distant also-ran, much beloved by then by most of the people who voted against him.

I am grateful to Mr. Patrick Keeffe, Office of Public Affairs at Cooper Union, for his counsel and to Heather Moore, Special Collections, UH Library, for suggesting I do an episode on Cooper.

See also, the Wikipedia article on Cooper.

clipart