Victorian Working Women

Today, a parable about social equity. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Victorian England had a strong economy, and her booming industries demanded labor. Poor women and children were a rich source. So women shoveled coal, made bricks and forged iron. They sold their backbreaking labor for a few shillings a week.

Poor women were completely separate from the English life we read about. Not even Dickens told the worst of it. The social system so separated them from the lettered upper class that a gentleman wasn't even supposed to speak to a poor woman.

Arthur Munby, an important member of the Ecclesiastical Commissions in London, was fascinated by working women. He was drawn to them. He tracked them, sketched them, wrote about them, and collected their photos. His work left us a rich record.

So we're able to look through his eyes. What we see are strong, handsome, functional women -- straightforward women who made a peculiar mockery of Victorian manners and affectation. No wonder Munby was attracted. They really are striking.

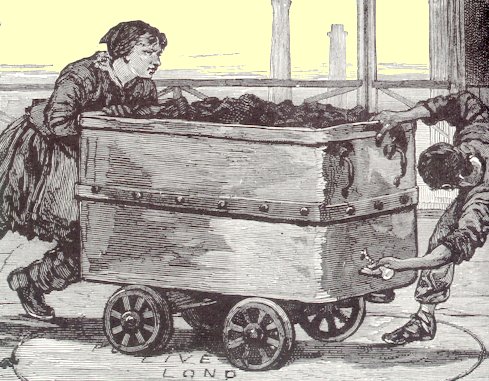

Now the plot thickens. In 1874 a London tabloid told about women working in the mines. It painted a terrible picture. Women worked as bare-chested beasts of burden pulling coal carts deep in the shafts. The pit brow girls wore trousers like men. That was even worse. The magazine called for reform.

Munby was appalled. He'd struck up friendships with those women. He knew and liked them. He wrote to a select Committee of Parliament recommending that they be allowed to continue. They needed and enjoyed their work. Although he didn't say it, he clearly felt they were an endangered species under attack.

Munby was especially attracted to a working woman named Hannah Cullwick. She was a "maid-of-all-work" in his own household. That meant she did any dirty job in a large house. It was back-breaking labor. Hannah was a tall, well-built woman.

In 1873, Munby and Hannah married. But he had to keep the marriage secret. It would've ruined him socially. So at home, she stayed the servant. When they traveled abroad, she was his well-dressed Victorian lady. He carried matched pairs of photos of Hannah. She's dressed as a servant on one side and as a fine lady on the other. Another pair shows her as a bonnetted fashion plate and as a lamp-blacked, half-naked chimney sweep.

It's no surprise that they grew distant in the last 30 years of such a marriage. After all, Munby was as damaged by that paralyzing social order as Hannah was. He wrote poetry about the innate equality of rich and poor women. But, in the end, tyranny degrades master and slave alike. And we wonder: Did either one have any way out of the terrible net they were both caught in?

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Hiley, M., Victorian Working Women: Portraits from Life. Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, 1979. Davidoff, L., Class and Gender in Victorian England, Sex and Class in Women's History (J.L. Newton, M.P. Ryan, and J.R. Walkowitz). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Chapter 1.

Munby and Cullwick married in 1873. She remained his shadow wife until she died in 1909. He died the following year. In his old age, Munby wrote the following statement:

It was a marriage of two who came together as it were from opposite poles, with a full and lasting conviction that they were made for each other; and the the contrast between them in station, in knowledge and experience, in outward seeming, was itself an evidence of the fact. It was a marriage of two enthusiasts: she, an enthusiast for her own class and calling, its ways, its dress, its manners; he, a sharer in that enthusiasm of hers, and an idealist, to whom she was the only woman who could fulfil his ideal and who did fulfil it.

He kept his unrealistic -- even self-deceptive -- idealism to the end, even though they'd lived apart for much of the marriage.

I thank Margaret Culbertson, UH Architecture and Art Library, for suggesting the subject and providing the Hiley source.

clipart