Mimetic Architecture

Today, we talk to automobiles. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I suddenly see that a whole architectural movement has come and gone in my lifetime. It arrived about the time I was born. Then it got away when I wasn't looking. It was a new architecture of instant communication.

You see, we lived in a brave new modern world in 1930. Our new machines had transformed us. Now cars whizzed across America on two-lane concrete highways. We were linked with one another as we'd never been. If you didn't drive, you hitch-hiked. Cars had become not only a 20th-century medium of communication, they'd become a metaphor for communication.

So we spoke to cars. Burma Shave signs hailed them as they passed. For a thousand miles either side of Wall's South Dakota drug store, signs told of that kitsch oasis on the road ahead.

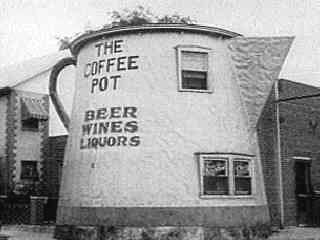

Then, a wild new architecture of communication came out of California. Suddenly you could buy lemonade from a building shaped like a lemon -- ice cream from an igloo --- film from a shop shaped like a camera. Buildings also took forms without rhyme or reason -- diners shaped like boxing gloves, zeppelins, dogs, and pumpkins. Pure means for catching a driver's eye.

Architecture is supposed to be more subtle than that. It should tell its function indirectly. But there's little time for subtlety at 60 miles an hour. We did what medieval businesses did 500 years ago for a different reason.

You didn't find a tavern's name, "Head of the Horse," written over the door of a medieval inn. Too few people could read. Instead, you saw the carved head of the horse itself.

California rediscovered that childlike directness. The state had already declared its architectural independence with Spanish Colonial adobe and stucco. Next it'd moved on to exotic themes -- Grauman's Chinese Theater and the Aztec Hotel. California had reached for the splendor of the silent movies.

Now, in the 1930s, California moved all the way to Wonderland. A 1936 Los Angeles Coca-Cola Company was shaped like a great ocean liner. You entered a huge coffee pot to drink coffee. Sometimes form followed function as doggedly as your shadow follows you. Sometimes function was as irrelevant as a day-dream.

But it was more than just cuteness. It was a way to make the break so we could begin again. The new cars told us we had to reorder our lives. We answered in the language of architecture.

For a season, we talked to cars. Now we take them for granted and wait for the year 2000. What it holds, we cannot know. Only one thing is sure: Our children will one day talk to machines we never imagined, in tongues as strange as these.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Heimann, J., and Georges, R., California Crazy: Roadside Vernacular Architecture. Tokyo: Dai Nippon, 1985.

Margolies, J., The End of the Road. New York: Viking Press, 1977.

Liebs, C.H., Main Street to Miracle Mile: American Roadside Architecture. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1985.

Venturi, R., Brown, D.S., and Izenour, S., Learning from Las Vegas. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1972.

This kind of representative architecture is called mimetic or programmatic. I'm grateful to Margaret Culbertson, UH Architecture Librarian, for her help with this episode.

clipart

clipart

Two typical coffee-pot coffee-shops falling into latter day disrepair

Mimetic architecture, forgotten and bypassed, on a Texas backroad (Photos by John Lienhard)