Stereoscope

Today, we meet the 19th-century grandparent of virtual reality. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Our family stereoscope was the great delight of my childhood. A stereoscope was a viewing device you held up before your face. You looked through two lenses, one for each eye, at two almost identical pictures, mounted side by side.

Your eyes merged two images into one. As they did, the picture jumped out in three dimensions. It was a stunning effect.

Movie houses tried to use the same trick after WW-II. Two pictures, in two colors, were slightly offset. They were blurry to the naked eye. But glasses with red and green lenses obstructed one image in each eye. The result was a crude version of what we used to see in stereoscopes. But now it moved.

The underlying idea is at least as old as Aristotle. He knew that our two eyes report different views. By putting those views together, we perceive depth. The electrical pioneer Charles Wheatstone first showed how we could use that fact.

In 1838 Wheatstone jolted the Royal Society by creating an illusion of three-dimensionality. He showed people two slightly offset line drawings through separate lenses.

But he could do no more. Then, a year later, François Arago announced Daguerre's invention of photography to the French Academy. Wheatstone, a foreign member of the French Academy, reacted to Arago's announcement. He asked for photographic images in stereo.

The French produced complex devices. When another Englishman named Brewster created a much simpler stereoscope in 1849, England wasn't interested. Brewster had to cross the Channel to find French lens-makers who would market his invention.

After that the stereoscope came out of France and emerged in the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibit. England finally caught on to the wonder of it all. Soon everyone had stereoscopes.

There were problems. Stereoscopic pictures made fine pornography. Erotica became a major industry. The public was officially outraged. In 1859 Baudelaire, whose poetry was not exactly G-rated, led the assault on shady pictures. That was the same Baudelaire who, seven years later, wrote in Les Fleurs du Mal: "What do I care that you are good? Be beautiful! And be sad."

But the pictures that delighted me as a child were pyramids in Egypt, cheeses in Holland, Rough Riders in Cuba. No longer flat images, but places that wrapped around me and fed my dreams.

The new visual media, movies and TV, drove stereoscopes out. Now, I suppose, we wait for their 21st century offspring, for virtual reality, to bring 3-D back -- stronger than ever.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Buerger, J.E., French Daguerreotypes. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989 (see especially, but not exclusively, Chapter 8.)

The following sources provide additional examples and details about the supporting cast:

Gernsheim, H., and Gernsheim, A., Daguerre, L.M.J., Cleveland: the World Publishing Company, 1956.

The Daguerreotype: A Sesquicentennial Celebration (John Wood, ed.). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1989.

I am grateful to Margaret Culbertson, UH Library, for isolating fine materials on Daguerreotypes and drawing my attention to them. She also provided the stereoscope (or stereopticon) image below.

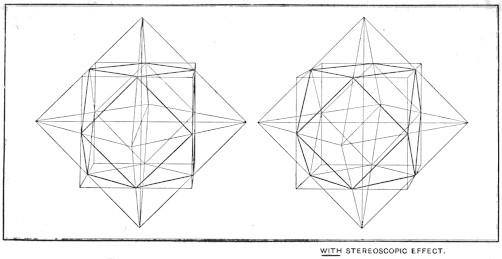

Another, perhaps more familiar, word for a stereoscope is stereopticon. Many of the episodes on this website are illustrated by stereopticon pictures. They may be found by searching on the word stereopticon. Below is a stereopticon card, not taken from a photo, but rather a drawing whose purpose was to display, in three dimensions, an inscribed polygon. Notice how the left and right sides of the picture offer slightly different perspectives -- just as either eye would see the image.