Guillotine

Today, heads will roll on the Engines of our Ingenuity. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We've praised technology enough on this program. The time has come to speak of darker things. Today let's look at the guillotine. Beheading has an odd history. It's all mixed up in class distinctions. In ancient Greece, Xenophon singled it out as a noble punishment. The Romans, who did pretty horrible things to common criminals, also saved decapitation for nobler folk. They called it capitis amputatio.

William the Conqueror brought beheading to England, where it was also set aside for nobility -- for people like Lady Jane Grey and Anne Boleyn. When the English beheaded the lower classes, it was only to finish off a victim who'd first been tormented in ways too nasty to talk about here.

The only reason for mechanizing such a seldom-used punishment was that axemen were sometimes inaccurate. Victims, after all, paid executioners a gold coin so they'd cut cleanly. A few early beheading machines were tried out. The sixteenth-century Scots used a device coyly named the Maiden, and an English machine called the Halifax Gibbet saw some use.

But it took the egalitarian French Revolution to bring beheading to the common man. Joseph Guillotin was a physician and a member of the Constituent Assembly in the early days of the French Revolution. In 1789 he got a law passed requiring that beheading machines be made so that, and I quote,

... the privilege of decapitation would no longer

be confined to nobles, and the process of execution

would be as painless as possible.

The machine was built, tested extensively on dead bodies, and turned loose on common criminals in 1792. Of course, once this was done, it became all too easy to dispose of counterrevolutionaries, and the slaughter called the Reign of Terror followed.

The American adventurer and inventor Count Rumford gave an interesting footnote to Guillotin's invention. Rumford married the widow of the famous chemist Antoine Lavoisier, who'd been among the thousands who died on guillotines. But a few years before his marriage, Rumford wrote, "I made the acquaintence of Monsieur Guillotin the contriver of the two famous Guillotines. He is a physician, and a very mild, polite humane man."

This may all seem quite ghoulish, but the point is clear enough. It is that we technologists are obliged to think twice when we're given the chance to sanitize death. When all is said and done, little separates gentle Dr. Guillotin's beheading machine from -- say -- the development of the neutron bomb.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Kershaw, A., A History of the Guillotine. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1993.

This episode has been considerably revised as Episode 1448.

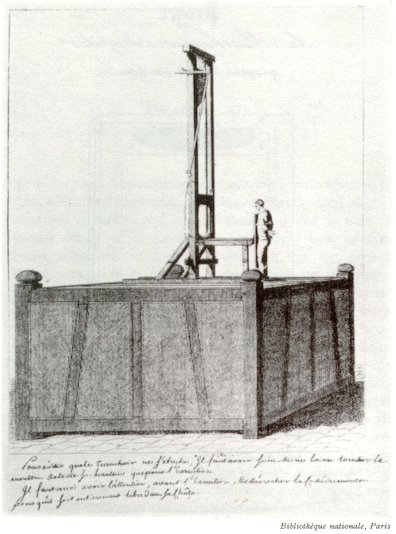

The first known representation of a Guillotine (1792)