Hiram Maxim

Today, we look within a great inventor and find a little boy playing at war. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

At the end of the last century the American inventor Hiram Maxim presented himself to the police in Petersburg, Russia. He was there to sell his new Maxim machine gun to the Czar.

"Your name is Hiram. You're Jewish," said the officer.

"I am not. My people were puritans," said Maxim.

"Then what is your religion?"

"I never had need of one," Maxim snorted.

"Well, no one can stay in Russia without a religion!"

"Very well," Maxim replied, "Put me down as a Protestant."

"And that," he tells us, "is how I became a Protestant."

Now a Protestant, Maxim went on to become a Sunday-school teacher. But meanwhile he sold vast numbers of his guns to Russia. Russia soon went to war with Japan, and, Maxim proudly tells us, "more than half the Japanese killed in the late war were killed with the little Maxim Gun."

Maxim was born in Maine in 1840. He was drawn to invention early in life. He worked with gas illumination, then electricity. He developed electric lighting systems even before Edison.

In 1883 a friend told him, "Hang your electricity. If you want to make your fortune, invent something to help these fool Europeans kill each other more quickly!"

Maxim took the advice. By 1885 he'd invented the first single-barrel machine gun. This "Maxim Gun" fired 666 rounds a minute, and it changed warfare. The Russo-Japanese War was a storm warning of the slaughter we'd see a decade later in WW-I.

The Maxim Guns (and nastier guns that followed) made Maxim's name. They also gained him an English knighthood. By then he was an English citizen and a friend of royalty.

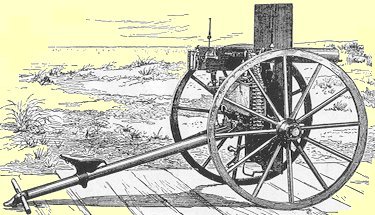

Early Maxim gun. From the 1888 Harper's Magazine

Yet guns were only another way-station for a very fertile mind. In 1891 Maxim began work on a huge flying machine. It was driven by two 180-horsepower steam engines of his own design. It was a biplane with a wingspan of over 100 feet.

He used restraining rails to keep the plane from getting more than a few feet off the ground in test runs. In 1894 the pilot did lift into the air --then crashed and damaged the plane.

Maxim lost interest after that. Later he said he'd been first to fly a man off the ground. He wished he'd had one of the new internal combustion engines and had built a smaller plane. Of course, that's what the Wright brothers did nine years later.

One of Maxim's last inventions was an effective bronchial inhaler. Critics took him to task for leaving war machines to work on medical nostrums. He was defensive about that.

For Maxim's whole life had been a vacant-lot war game. For him, and the generals and princes he ran with, war was no more real than becoming a Protestant was. He was, to the end, a brilliant little boy at play.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Maxim, H., My Life. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd., 1915.

Angelucci, E., World Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. 1982, pp. 38-40.

Hogg, I., The Weapons that Changed the World. New York: Arbor House, 1986, pp. 22-25.

For more on Maxim's airplane see Episode 210.

From the January, 1895, Century Magazine

For a full size image click on the thumbnail above

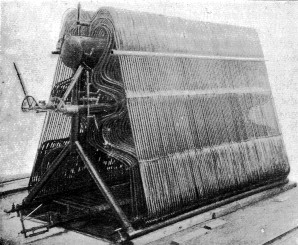

From the January, 1895, Century Magazine

The steam boiler for Maxim's airplane