Bush's Analog Prediction

Today, let's see how a 50-year-old prediction works out. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Just before WW-II, Vannevar Bush directed the NACA -- NASA's forerunner. Then he took over Roosevelt's new Office of Scientific Research and Development.

In 1945 he published an Atlantic Monthly article. He tried to predict future technology. How right he was in the big picture! How wrong he was in one fundamental detail!

During the '30s, Bush had taken the analog computer about as far as anyone could. His Rockefeller Differential Analyzer was the grandest computer ever built. Yet by 1945 the new digital computer had made it obsolete. The analog/digital issue is the only thing that mars Bush's otherwise stunning prediction.

We use the word analog for processes analogous to the continuous ones we experience in nature. A digital computer is more abstract. It breaks text, or any other kind of information, into sequences of plus/minus signals.

The central problem that drove Bush's vision was the mounting flood of information. That was only going to get worse. How will we cope with it, he asked. His analog answer was microphotography and optical scanners -- all aided by the analog computer. Bush never whispers the words "digital storage."

Still, the computer is the lynchpin of his prediction. He sees with utter clarity that it's going to permeate information-handling in everyday life. For example, he takes us to a new department store.

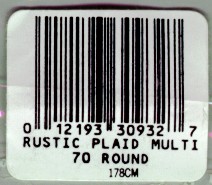

A customer hands the clerk his private punched card. The clerk adds a price card from each item. He lines them up in a slot. The machine automatically corrects the inventory. It charges the customer. It prints a receipt. Bush saw the credit card and the bar-code coming. But he saw them in analog form.

There's more. He says we'll encode speech. He's vague on how we'll do that, though. Small wonder! We're only doing that now with digital sound storage -- more plus/minus signals.

Vannevar Bush's magical vision saw that our next great intellectual frontier lay in managing a flood of information. In 1945, the other futurists turned their crystal balls on travel and power production. Bush ends by saying,

[Man] has built a civilization so complex that he needs to mechanize his records more fully if he is to push his experiment to its logical conclusion [without being bogged down by] his limited memory. [He must] reacquire the privilege of forgetting [all the] things he does not need ..., with some assurance that he can find them again if they prove important.

The other prophets didn't see that the twin issues of information retention and access would dominate the end of this century. But Bush did, and he did so with eerie clarity.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bush, V., As We May Think. The Atlantic Monthly, July 1945.

The Vannevar Bush article was urged on me by Judy E. Myers, University of Houston Library, in the context of an ongoing conversation about information access. See also Episode 27 on Bush's Differential Analyzer.

Where Bush's idea came to rest