Bush-bushnell

Today, a curious Dr. Jekyll, Mr. Hyde story. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The year is 1824. The town is Warrenton, Georgia. Gentle Dr. Bush has just died at the age of 82. He's lived here for 30 years. He practiced medicine for the last 20 of those years. He also taught both religion and science at the local Warrenton Academy.

Dr. Bush was respected, but he was a very private man. We knew he was from New England and that he'd lived in France before he came here. That's about all we knew.

Now his executors are in for a surprise. First they find wooden pieces of a submarine prototype in Dr. Bush's workshop. His papers are even more startling. They find that Dr. Bush wasn't really Dr. Bush at all. He was Captain David Bushnell, once a member of the Continental Army's Corps of Engineers.

This gentle doctor was the first military submarine maker. Bushnell began as a bookish Connecticut farmer. When he was 29, his father died. So he sold the farm and went to Yale. For four years he studied science, and he built his man-powered sub.

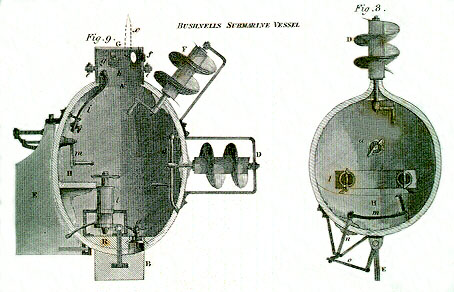

He called his boat the Turtle because he'd made it from two hollowed-out wooden slabs. They looked like huge turtle shells. David Bushnell's brother Ezra learned to pilot the submarine.

David readied the Turtle for action against the English in 1776. Then Ezra fell ill. David had to start from scratch.

He trained Ezra Lee, a gunnery sergeant, to sink the English man-o-war, Eagle. Lee did the best he could. He managed to get under the Eagle. But when he tried to anchor the torpedo, his drill hit an iron fitting. Dawn found Lee exhausted. He dumped his warhead in the bay and ran. The charge went off harmlessly. Still, the English fleet bolted. It put to sea.

But that didn't satisfy David Bushnell. He turned his fury and frustration on Lee. Lee fled back to his outfit, and Bushnell tried to smuggle the Turtle away from the British on a sloop. An English frigate spotted the sloop and sank it. So our first submarine came to rest at the bottom of the sea.

Bushnell had used up his fortune by now. He finished the Revolution designing mines. Then he went to France to sell his submarine design. He also failed at that. By 1795, thoroughly disillusioned, Bushnell came back to America, to Georgia, as Dr. Bush. He gave the rest of his life over to teaching and healing.

It'd be another forty years before a submarine would sink a ship -- ninety years before wholesale slaughter would begin. Gentle Dr. Bush never had to see the fruit of David Bushnell's bold, visionary experiment.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Abbot, H.L., The Beginning of Modern Submarine Warfare (Frank Anderson, ed.). Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1966. (A facsimile of an 1881 pamphlet)

Submarine historian Brayton Harris offers the following interesting footnote to the Bush-Bushnell story:

We presume that Bushnell went to France, and may even have met with Inventor Robert Fulton who demonstrated his reasonably-practical submarine, Nautilus, for the French at the turn of the nineteenth Century. There is some evidence that he may have been directly or indirectly helped by Bushnell there or in England.

We know there had to be a pretty strong connection because Dr. Bush's housemate in Georgia was fellow Yale grad and former congressman/senator Abraham Baldwin. Baldwin's brother-in-law was Yale graduate Joel Barlow, with whom Fulton had lived for some seven years. Barlow and his wife had taken Fulton under their wing while he was trying to find himself. Barlow worked with Fulton in France, in 1797, on perfecting a self-propelled "torpedo." Barlow apparently helped Fulton to get a commission as a rear admiral in the French Navy in summer of 1800 (to legitimize his planned attack on the British enemy).

From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia

Artist's conception of Bushnell's Turtle, 56 years after the fact