Old Knowledge

Today, thoughts about a conflict that scholars face. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

An eminent engineer once said to me, "John, our field suffers because we forget primary sources. We only read papers that were written the day before yesterday."

The importance of that remark came home to me a few years ago when my son John began studying fluid mechanics. I suggested he might try to solve an old problem that no one had figured out how to do. It was this:

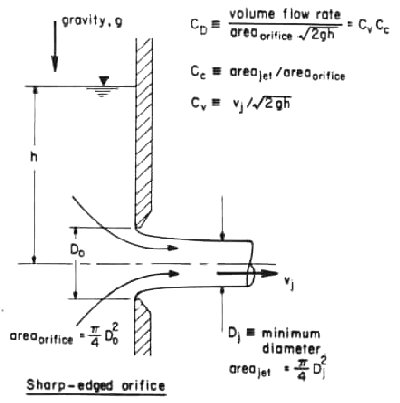

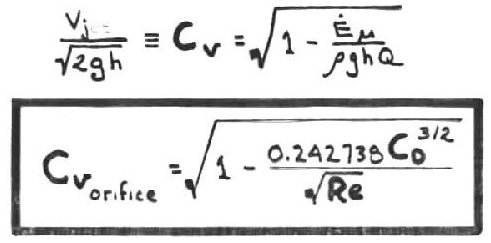

When water flows through a round hole in a plate, two things happen: The jet contracts to a diameter smaller than the hole. And water viscosity slows the jet. Both effects reduce the outflow. Textbooks say the jet slows about two percent, but no one had ever predicted the slowing mathematically.

So John made the prediction. The trouble was, he showed viscosity has almost no effect on jet speed. He contradicted what everyone thought they knew. Something was wrong, so he went looking.

The trail led back to a 1940 paper. The authors had carefully measured the net reduction in flow out of a hole. But they'd lumped contraction and slowing together.

They referred to measurements in an old paper, written in 1906. They found a flaw in the old contraction measurements. After that, no one else bothered to look at the 1906 paper.

But John did look at it. Then everything came clear. This century-old paper gave the only measurements of viscous slowing anyone had ever made. It was beautiful work. Maybe the contraction measurements were flawed. But it was now crystal-clear that viscosity had almost no effect on speed.

After 1940, textbook writers misread the 1940 paper without looking back at the 1906 paper. Now every textbook says that two percent of the speed is lost. Every textbook is wrong.

That's what happens when we forget primary sources -- when we bury the past. It's a story we can tell a hundred different ways. This kind of thing happens all the time.

We face a hard problem when we try to do something original and new. We have to shed the past to create the future. Yet the past contains such riches of knowledge. The most pernicious myth about knowledge is that it deteriorates with age. It does not, of course. And, when we lose the ability to remember, we defile what we do today. We rob our own best effort of its future.

That's an essential tension we face as we go after new knowledge. How do we use the past without letting it turn us into a pillar of salt? How do we think forward and look back at the same time? That's not an easy question. It's not easy at all.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lienhard, J.H., V, and Lienhard, J.H. (IV), Velocity Coefficients for Free Jets from Sharp-Edged Orifices. J. Fluids Engr., Vol. 106, No. 1, 1984, pp. 13-17.

Medaugh, F.W., and Johnson, G.D., Investigation of the Discharge Coefficients of Small Circular Orifices. Civil Engr., Vol. 7, No. 7, 1940, pp. 422-424.

Judd, H., and King, R.S., Some Experiments on the Frictionless Orifice. Engr. News, Vol. 56, No. 13, 1906, pp. 326-330.

The engineer who made the remark about primary sources is Neal Amundson, Professor of Chemical Engineering at the University of Houston. Amundson is the pioneer of modern mathematical technique in chemical engineering.

For more on this theme, see episode No. 597. We also discuss this idea further in a note under review: Myers, J.E., and Lienhard, J.H., The Fate of Knowledge.

From the Lienhard-Lienhard paper above

The configuration of a jet leaving a sharp-edged orifice

Velocity loss in an orifice