The Crossbow

Today, the crossbow -- and the problem of competing technologies. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The military crossbow showed up in the Battle of Hastings. It lasted about 300 years. Then it gave way to firearms.

In one sense crossbows were much older than Hastings. After all, they were just regular bows mounted on a grooved stock and fitted with a trigger. And the Roman siege catapult was really a large crossbow. But we didn't reduce that siege engine to a hand-held replacement for the bow and arrow until the Middle Ages.

Once we did, the crossbow evolved quickly. We strengthened the bow. Then we made it of spring steel. First we used levers -- then cranks -- to pull bow strings with forces of over half a ton. We soon had a terrible weapon with a range of over 300 yards.

In 1139, a Church council declared crossbows unfit for Christian use -- except against Infidels. In the next decades other councils repeated the ban. So Crusaders carried crossbows to the Holy Land, and they kept on developing the technology.

The crossbow became a regular part of military tactics. When the ban was inconvenient, kings forgot it. I suppose any enemy became an Infidel on the battlefield.

The crossbow's great test came in 1346 at the Battle of Crécy in Northern France. Edward III's English army met the French. The French had 20,000 mercenary crossbowmen and some of their own cavalry. Edward's troops carried English longbows.

The weather and terrain ran against the French. To load a crossbow you put the bow on the ground and crank the bow-string back. It takes firm ground and time. The ground at Crécy that day was mud. Even under good conditions, a skillful English archer with a manual longbow could loose 5 or 6 arrows while a crossbowman was still turning his crank. This day, the English riddled the crossbowmen 'til they fled into their own cavalry.

A newer weapon also made its debut at Crécy. It was probably the first major battle that involved firearms. Gunpowder wasn't a major player at Crécy. It was an omen.

A century later, the crossbow gave way to the gun. And we read a parable of technological progress at Crécy. The hottest technology -- the crossbow -- took the field with two competitors. The older of the two, the longbow, did better in an open field under bad conditions. The younger, the gun, was still ineffective at Crécy. But it wouldn't stay so for long! By 1585, the surgeon Ambroise Paré, sick of gunshot wounds, cried,

. . . we . . . rightfully curse the author of so pernicious an engine; [and] praise those to the skies, who endeavor by words and pious exhortations to [dissuade] kings from its use.

Well, no one ever dissuaded a king from using new weapons. And we never have done well at predicting how new weapons will fare.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Payne-Gallwey, Sir R., The Crossbow: Medieval and Modern Military and Sporting. New York: Bramhall House, 1958.

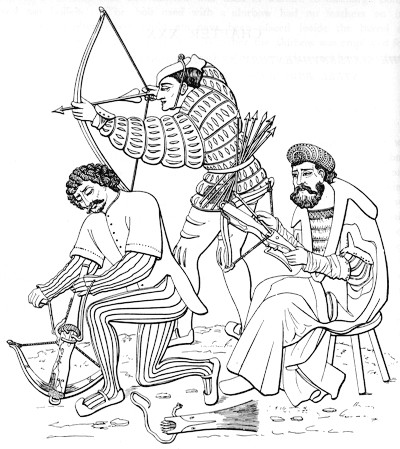

From Costumes of Mediaeval Christendom, 1840-1845, shown in the Payne-Gallwey source above

The kneeling and seated figures show how a crossbow is first drawn and then loaded. The standing figure, by contrast, suggests how much more rapidly a conventional bow may be used.

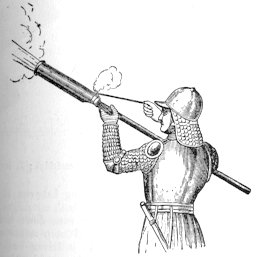

From the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica

An early hand gun, probably from a time not too long after the Battle of Crecy