Learning to Fly

Today, linger a moment -- before we get serious about flight. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It's 1911, and we've just learned to fly -- or have we? Don't forget: A few years later, in WW-I, nothing in the sky resembled the Wright Brothers' airplane. The Wrights had put the tail in the front and the propeller in the back.

So what was the best shape for a flying machine? It was soon clear you could get the three essential functions of lift, propulsion, and control in many ways.

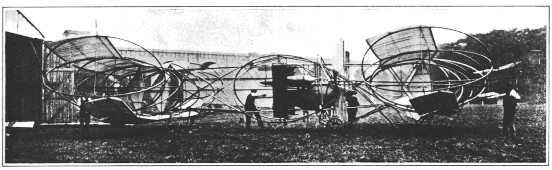

Now it's 1911 -- seven years after the Wrights first flew. Here's a magazine article on flight. The title is "A Chamber of Horrors." The writer shows us an array of experimental flying machines.

A visitor from another planet would never guess the common function of these mad engines of so much ingenuity. No two are alike. One looks like a dumbbell. Another, like your attic fan. Wings, if the airplane even uses wings, are strewn like straw about struts and engines. The author says,

Here is a problem for the psychologist to solve. Mechanics alone scarcely furnish the key ... These odd structures are claims staked ... on the hills of golden promise ...

He shows us the then-largest plane ever built. Two 80 HP engines sit in the middle of a crazy frame. It has four great wings -- two in front, two in back. He likes that one. He says,

The boldness of the ... execution, with the great hoops and sweeping curves suggesting the expert in Spencerian handwriting, almost disarms criticism, numbing it with the query: Can this be possible.

This new breed of inventors kept a crazy pace as they sifted and sorted. They tried everything. The mind flew, even if its fruit did not always do so.

Ten years from now, we'd settle on two or three configurations. In 10 years we'd be fine-tuning the compromise between two warring virtues -- control and stability. In 10 years, airplane building would pass from amateurs to professionals.

But right now there are no rules. It's open season for the imagination. We suffer a dozen failures for each glorious success. Yet we know the game is worth the candle.

The author ends with a list of recent fatal accidents. Of course we'll have to quit playing around. But not now -- not while we're having so much fun.

There was a pot of gold at the end of this rainbow of machines. Flight developed five times faster than automobiles did. Our madcap willingness to fail guaranteed far faster success for flight -- than we had any right to expect.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Karup, M.C., A Chamber of Horrors: Wild Designs in Flying Machines. Early Flight: From Balloons to Biplanes. (Frank Oppel, ed.) Secaucus, NJ: Castle, 1987, Chapter 31.

Image from the original article cited in the source above

The author suggests that this looks like an exercise in penmanship