Heatley & Penicillin

Today, we meet a man who could grow things and make things. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

My 1970 encyclopedia article on penicillin says that Alexander Fleming discovered it in 1929. Ten years later, it says, Howard Florey formed a team at Oxford University. They figured out how to produce it. The article mentions no one else.

In 1990, Oxford broke precedent to give an honorary doctorate to Norman Heatley for his work on penicillin. Never before, in 800 years, had Oxford given an honorary doctorate.

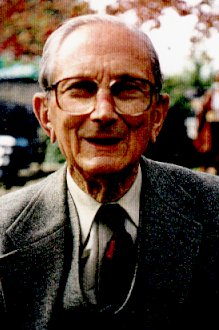

So who was Heatley? Author Carol Moberg tracks him down in his garden in England. He's a slight man, now 80, and still active. He trained as a biochemist, but his specialty is growing things. He leads Moberg through his yard. He shows her his plant creations. Here's a special four-tiered, horizontally growing pear tree, for example.

Heatley was part of Florey's team. Florey had set out to create the first antibiotics. Heatley's task was to produce enough penicillin for the group to study. Not an easy job! Penicillin is terribly unstable and hard to make.

But Heatley had just the right abilities. He knew how to improvise. He knew how to use his hands. He wasn't just a scientist. He had the inventive sense of an engineer. First he created means for growing penicillin and measuring its output. Then he figured out how to reuse the special fungus it grows in.

But that wasn't enough. We have to separate penicillin from the fungus. That'd stymied everyone for 10 years. Heatley invented a new extraction process to get the penicillin without destroying it. Finally, he used hospital bedpans as mass-production growth chambers.

The Oxford team announced penicillin as an antibiotic in 1940. Their paper had six authors, listed in alphabetical order. Heatley was the fourth.

This was the eve of WW-II. America picked up Heatley's techniques. We mass-produced penicillin during the war and saved countless lives with it. Finally, in 1945, Fleming and Florey got the Nobel Prize in medicine for their part in the work.

Now, 50 years later, Oxford honors the quiet man who made all that possible. And Heatley says, diffidently:

This is an enormous privilege since I am not medically qualified. ... I was a third rate scientist whose only merit was to be in the right place at the right time.

But we know better. We know we've underrated making and doing. We know America suffers from too little making and doing today. It's high time we honored this man who showed us how to make the stuff that's saved so many lives ever since.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Moberg, C., Penicillin's Forgotten Man: Norman Heatley. Science, Vol. 253, 16 August, 1991, pp. 734-735.

The 1945 Nobel Prize in Medicine included Ernst Chain as well as Fleming and Florey. Chain was a chemist who'd worked on medicinal properties of penicillin. He was also first author on the paper mentioned in the text.

For more on penicillin, see Episode 1015.

(Photo courtesy of Mary Krinsky)

Norman Heatley

(Photo courtesy of Mary Krinsky)

Heatley with his horizontal growing pear tree