Submarine

Today, we look at a surprising claim about Colonial technology. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Historian Alex Rowland suggests that Colonial inventiveness was less than it's cracked up to be. He begins by directing our attention to Bushnell's invention of the submarine.

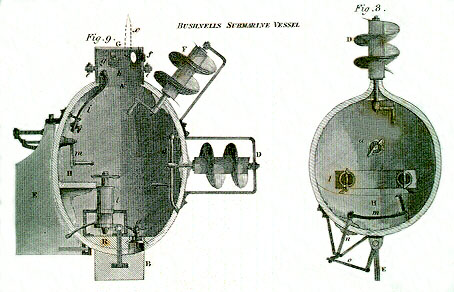

Bushnell was one of our most famous Colonial inventors. In 1776 he built a one-man, hand-crank-powered submarine called the Turtle. The Turtle swam under the British ship Eagle and fastened a charge to its copper-clad hull. When the charge exploded, it did little or no damage, but the potential of this new instrument of war was made clear enough.

Still, Bushnell abandoned the Turtle a year later, and this time he went at the British ships moored at Philadelphia with floating mines. Once more he was more impressive than successful. Colonial composer Francis Hopkinson wrote about the reaction on the British-occupied shore:

Some fire cried, which some denied,

But said the earth had quak-ed.

And girls and boys, with hideous noise,

Ran through the streets half-naked.

Bushnell has ever since been hailed as the father of the submarine and as a great American technological genius.

Rowland points out that the Colonies were very well informed about European technology. Bushnell, it seems, worked on the Turtle at Yale University; and the Yale library had the English Gentleman's Magazine -- a kind of 18th-century Scientific American. I've looked at the 1747 volume of the Gentleman's Magazine, and, sure enough, there's a short article with European sketches of how submarines might be built. They have many of the features of Bushnell's Turtle.

It's all too easy to start embroidering this theme. American successes with the steamboat, the electric light, the Erie canal, the telegraph -- they all followed European inventions of these technologies. Rowland argues that the United States didn't actually originate many major new technologies until the 20th century.

And yet we put flesh and blood on those skeletal ideas. Bushnell was first to put a living, breathing man under water in combat. The confident go-and-do-it mentality of Colonial and 19th-century America displayed real inventiveness -- and a real component of genius.

Do we see this drama being replayed today? Forty years ago we sneered at Japan for making second-rate copies of our technologies. Today, we ask how on earth they develop our inventions so rapidly and so well. Tomorrow, if we don't rediscover our own childlike verve and enthusiasm for both invention and development, we'll be looking to Japan for seminal ideas.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Abbot, H.L., Beginning of Modern Submarine Warfare (Frank Anderson, ed.). Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1966 (Facsimile of an 1881 pamphlet).

Roland, A., Bushnell's Submarine: American Original or European Import? Technology and Culture, Vol. 18, No. 2, April 1977, pp. 157-174.

This episode has been revised as Episode 1385.

(From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia)

Artist's conception of Bushnell's Turtle, 56 year after the fact

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library)

Schematic diagram of a submarine from the 1747 Gentleman's Magazine, probably based on a design by the Dutch/English scientist Cornelius Drebbel