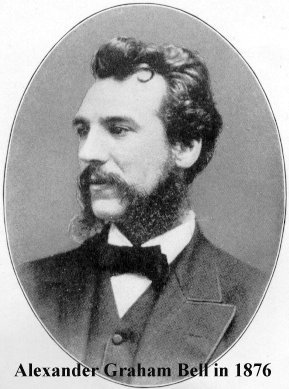

Alexander Graham Bell

Today, we find out what Bell did after he invented the telephone. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Alexander Graham Bell was born in Scotland in 1847. He died seventy-five years later in Nova Scotia. When he was only 25, he opened a school in Boston for teachers of the deaf. A few years later, he married a very bright young deaf woman named Mabel. He also began work on an instrument to help the deaf hear. He perfected the telephone.

Alexander Graham Bell was born in Scotland in 1847. He died seventy-five years later in Nova Scotia. When he was only 25, he opened a school in Boston for teachers of the deaf. A few years later, he married a very bright young deaf woman named Mabel. He also began work on an instrument to help the deaf hear. He perfected the telephone.

In 1885, the Bells visited Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia. It was perfect. They built a laboratory there and passed the next 37 years in a rich life together.

The telephone is such a huge monument to Bell's inventive genius. We overlook the outpouring of invention that followed it on that lovely windswept island.

For example, Bell developed an early version of the iron lung. He invented the ancestor of the FAX machine. He bred a strain of 6 and 8-nippled sheep to do better at nursing lambs. He pushed for the use of ethyl alcohol in place of fossil fuels.

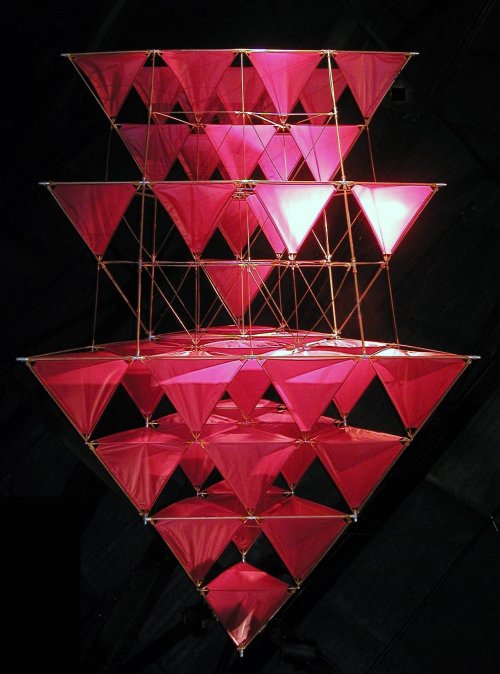

Two fascinations marked Bell's whole life. One was his concern for the deaf. The other was flight. First he made a series of exotic kites formed out of tetrahedonal elements. Buckminster Fuller learned about Bell's tetrahedrons after he'd made his geodesic dome the same way.

Here are old photos. Helen Keller, a friend and house guest, helps him fly a huge kite. His wife, Mabel, stands in an abstract tetrahedron kite frame. She leans out to kiss Alexander. It is a gentle life with fine texture and form.

Later, Bell flew people in his kites. He built a 70-foot tower from his tetrahedrons. Then he went on to build airplanes.

Finally, his studies of aerodynamics led him to invent the hydrofoil. That work culminated in his HD-4. The HD-4 was a hydrofoil driven by two airplane propellers. It went over 70 miles an hour. For years it was the fastest thing on water.

A wonderful mood surrounds all this invention. Photos show Bell with children -- always playing with children. They show Mabel, pulled halfway off her feet, measuring the stress in a kite line. Raw affection wells up everywhere. Bell writes to Mabel when she sits for her portrait:

... lay ... siege to [the artist's] heart ... that those beautiful eyes and sweet face I value so much may grow out of the canvas.

So what did happen after the telephone? A warm, inventive man kept right on creating. He left us a legacy of invention that reached far beyond the telephone. That legacy flowed from a great mind. But it flowed from a very large heart, as well.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Eber, D.H., Genius at Work: Images of Alexander Graham Bell. New York: A Studio Book, The Viking Press, 1982.

And, just for the fun of it, you might also be interested in a fictionalized novel about Alexander and Mabel Bell on Cape Breton:

McMahon, T., Loving Little Egypt. New York: Viking, 1987.

A model of a Bell kite on display at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City N.Y.