A Visit to the Taj Mahal

Today, a monument speaks to us. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It's a warm day. Our hired car threads along the ever-filled two-lane road. We pass three camels lurching under great loads of straw. We see an elephant moving grain sacks with his trunk. We honk at a 3-wheeled taxi. Passengers sit on its roof and hang from its sides. We make the unforgettable 4½-hour, 120-mile pilgrimage from New Delhi to Agra.

Another engineer and I are going to see the Taj Mahal. Right now, I don't care if I ever get there. The trip is hypnotic. But we do get there, and we enter the main portal.

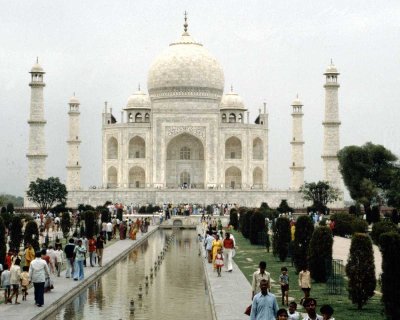

And there it is! It gleams a third of a mile away -- at the other end of the long reflecting pool. We leave the roiling outer world of India and enter an eerie inner space.

The Taj Mahal is a tomb. In 1631 Mumtaz Mahal died in childbirth. She'd been the Shah's consort. They'd been more than man and woman in any usual sense. They'd made a connection two people are seldom privileged to make. Her loss was devastation.

How do you cope with such grief? If you can't find language to express it, it can destroy you. So the Shah arrayed the great architects of the Islamic world. Out of them, one rose like cream. He was Ustad Isa from Persia.

He conceived a monument -- immense but restrained. Its dome rises 240 feet. The four minarets are 140 feet tall. We all know the Taj is made of white marble. We've all seen photos. But up close you find a delicate tracery of semiprecious stone inlay.

It is both a jewel and its setting. The gardens, the red sandstone outer walls, the entry portal, the great pool -- they all create an artistic whole. The most telling praise for the Taj comes from critics who call it "too feminine!" Its design is a delicate perfection.

Of course it meant exploitation. 20,000 people worked 22 years to build it. It cost 40 million rupees. But in the end that gift of serenity has touched hundreds of millions of us.

The Taj reminds us that technology and art are inseparable. Both flow from the deepest recesses of human feeling. Separate what we feel from what we make, and we'll make a bad world -- a world that doesn't fit.

For centuries, the Taj has transmuted the Shah's love and pain into a glimpse of human glory. One last look, and we two engineers are back in the swirling world outside. But that world is changed. We two builders of external worlds feel it. Of course, it is really we who are changed -- by what we have seen.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Background material on the Taj Mahal may be found at the website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taj_Mahal

clipart