Tyndall & Unruly Nature

Today, let's look inside a 19th-century scientist. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The great experimental physicist John Tyndall holds an eerie fascination for me. He was born in Ireland in 1820. He began doing the engineering of railway systems. And all his life he was drawn like a moth to the flame of Romantic poetry.

His physics lay squarely between those two powerful forces -- between the material engines of external reality and the inner engines of the Romantic mind. He made constant reference to the wild forces of nature. His physics grew lyrical when he described glaciers or the erratic behavior of flames.

Listen to this curious sentence from the preface to his text on heat:

I have ... tried to show [how physicists] pass from the world of the senses to a world where vision becomes spiritual, where principles are [formed], and from which the explorer emerges with [concepts] to be approved or rejected as they coincide] with sensible things.

Tyndall bends our usual view of the scientific method to the language of the Romantic poets. The scientist, he says, starts out in the realm of the physical senses. But the creative act of shaping sense-data into concept is a spiritual one. Then he must bring concept down off the mountain -- back to the hard earth. There, he must put it to the test.

The Romantic poets shaped a new view of reality in the early 19th century. They told us that we create nature by dreaming nature. That sounds like tomfoolery at first.

But scientists and inventors soon saw what the Romantics meant. Just as a poem, or a machine, is a reality first shaped in our minds, so too is our concept of nature. What, after all, is nature before our minds give it its shape?

By the end of the 19th century physics was an intellectual marvel. Tyndall's name doesn't stand with those who followed -- with Maxwell, Boltzmann, or Planck. But he armed those giants. His astonishing eye for physical reality extended their outward vision. He, and others like him, also led science to the inner vision of the Romantics. In the end that twofold view did indeed create nature by dreaming up a whole new edifice of natural law.

Yet Tyndall was no fool. He also saw something that 20th-century philosophers would soon tell us. No man-made edifice of natural law will ever bring us to absolute truth. He says,

Thus, having exhausted science and reached its very rim, the real mystery of existence still looms around us. And thus it will ever loom -- ever beyond the bourne of man's intellect -- giving the poets of successive ages just occasion to declare that,

We are such stuff As dreams are made of,

and our little life Is rounded by a sleep.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Tyndall, J., Heat: A Mode of Motion. Sixth Ed., London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1880. (The first edition was published in 1863. I direct the reader especially to the Preface to the sixth edition and to pp. 535-536.)

Tyndall's book includes one passage I wanted to use in the broadcast episode but which was a too long. In it, he restates the first law of thermodynamics, which says that energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

The law of conservation rigidly excludes both creation and annihilation. Waves may change to ripples, and ripples to waves -- magnitude may be substituted for number, and number for magnitude -- asteroids may aggregate into suns, suns may invest their energy in florae and faunae, and florae and faunae may melt in air -- the flux of power is eternally the same. It rolls in music through the ages, while the manifestations of physical life, as well as the display of physical phenomena, are but modulations of its rhythm.

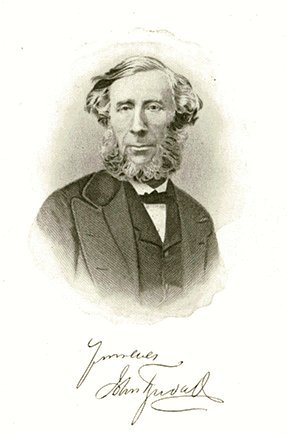

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

John Tyndall, from the frontispiece of his book,

Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers, 1874