Pins

Today, let's talk about pins. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Needles and pins, needles and pins,

When a man marries his trouble begins.

goes the old nursery rhyme. The lowly dressmaker's pin used to be a metaphor for the commonplace household necessities. Most clothes were made at home in the early 19th century; and dressmakers absolutely need pins.

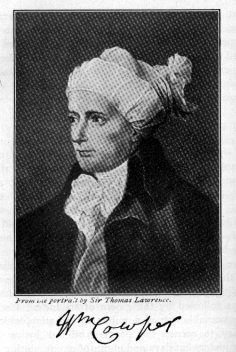

But pins were hard to make. People made them by hand in production lines, with each person doing one operation. The popular 18th-century poet, William Cowper, described a seven-man pin-production line in a poem that began:

But pins were hard to make. People made them by hand in production lines, with each person doing one operation. The popular 18th-century poet, William Cowper, described a seven-man pin-production line in a poem that began:

One fuses metal o'er the fire;

A second draws it into wire; ...

and which continued through to the finished pin.

But pin-making was actually more complex than Cowper made it out to be. The 18th-century economist Adam Smith described 18 separate steps in the production of a pin. Small wonder then, that pin-making was one of the first industries to which the early-19th-century idea of mass production was directed.

Steven Lubar identifies the first three patents for automatic pin-making machines in 1814, 1824, and 1832. The last of these -- and the first really successful one -- was filed by an American physician named John Howe. Howe's machine was fully operational by 1841, and Lubar justly calls it "a marvel of mechanical ingenuity." It took in wire, moved it through many different processes, and spit out pins. It was a completely automated robot driven by a dazzlingly complex array of gears and cams.

When Howe went into production, the most vexing part of his operation wasn't making pins but packaging them. You may have heard the old song:

I'll buy you a paper of pins,

and that's the way our love begins.

Finished pins had to be pushed through ridges in paper holders, so both the heads and points would be visible to buyers. It took Howe a long time to mechanize this part of his operation. Until he did, the pins were sent out to pin-packers who operated a slow-moving cottage industry, quite beyond Howe's control.

It's natural for us to glory in our grander inventions -- in steam engines and spaceships. But technology also serves us by easing the nagging commonplace needs that complicate our lives. Howe's ingenuity in making the lowly pin easily available was a very large contribution to 19th-century life and well-being.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lubar, S., Culture and Technological Design in the 19th-Century Pin Industry: John Howe and the Howe Manufacturing Company, Technology and Culture, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1987, pp. 253-282.

This episode has been revised as Episode 1295.