A View in Inner Space

Today, we try to judge a book by its contents instead of its cover. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

So many of my friends like to tell me about engineers. "Engineers are dull," they say. "Engineers are inarticulate." That sort of thing used to make me angry. Now I'm a little more sympathetic. I realize what it is they cannot see.

Long ago, I worked at the Pacific Car and Foundry Company in Seattle. We made accessories for tractors. We made winches, hitches, and booms for laying pipe.

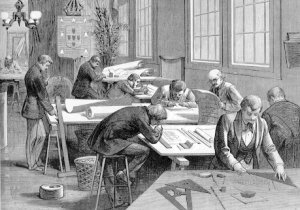

I worked with a seasoned designer. He wore a white shirt and a bow tie. He said almost nothing. You saw his authority and imagination only when he bent to a drawing board. Each time he put a pencil to that great spread of blue lined paper, there appeared some graceful machine that'd never been before.

I also worked at a drawing board, but this quiet man outclassed me. It was humbling to watch new machines pouring out of his mind. For years afterward, all up and down Oregon and Washington, I'd see his clean, compact tractor attachments. They hauled logs and dug trenches -- laid pipe and set posts. They improved the lives of millions of people who looked at my friend and saw no more than a clerkish fellow in a bow tie.

Today my wife handed me a magazine about new technology. Maybe there was a story I could use. It was frustrating. Here's an article about a topologist at Bell Labs. Communication systems pose problems like that of fitting spheres into a box. We see lovely pictures of stacked spheres and strangely sliced pies. But the math is too intricate. The pictures are too complex. I cannot tell it on the radio, so I turn the page.

Another designer makes robots for space vehicles. The light-weight extensible arms are complex accordion structures. His models are made of folded paper. They're more graceful and delicate than origami. But you can't describe them when you're limited to the stunted language of words.

I spend my days among people who live this life. I know the invisibility of the paintings they paint and the silence of the songs they sing. I've seen the beauty of their quiet dreams.

That designer in Seattle was a happy man. He was fulfilled. Oh, he faced problems. Not everything he touched turned to gold. But beating problems is just where creative people find pleasure.

So many people cannot see the things that old designer could see. But no matter. For he was the one building their civilization.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Discover, Special 10th Anniversary Issue, October 1990. See especially pp. 58-74.

A 19th century engineering drafting room