16th Century Clocks

Today, let's see what clocks have to tell us besides the time of day. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The mechanical clock was invented around AD 1300 -- give or take a little. Two hundred and fifty years later, clocks had become very sophisticated machines. Otto Mayr's book on the third century of clock-making -- The Clockwork Universe: 1550 to 1650 -- provides a remarkable insight, not just into the glorious clocks of this period, but into the nature of invention as well.

As machines go, clocks have an odd character. You wind them up and then sit back to watch them carry out their function. A well-designed clock goes on and on, showing the time of day without human intervention and without self-correction. And so the ideal clock -- the clock that we almost, but never quite, make -- became a parable of divine perfection.

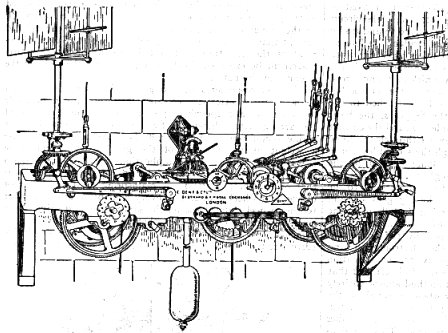

By the middle of the 16th century, clocks weren't just accurate; they were also remarkably beautiful -- adorned with stunning, but seemingly useless, mechanical trimming. Robots marched out on the hour and performed short plays. Extra dials displayed the movements of planets. Clocks were crowned with exquisite miniature gold, bronze, and silver statuary.

The intricate wheels and gears of these Baroque clocks became a metaphor for the solar system, for the universe, for the mind of man, and for the very nature of God. The best minds and talents were drawn into the seemingly decorative work of clock-making because clocks harnessed the imagination of 16th-century Europe.

All this was rather strange, because there was no need for precision time-keeping. Later, during the 18th century, the clock began to take its role as a scientific instrument -- especially for its use in celestial navigation. But in 1600 the clock was primarily an esthetic and intellectual exercise.

Our thinking is so practical today. We'd probably condemn this activity as a misuse of resources. But the stimulus of the clock eventually drove us to unimagined levels of quality in instrument-making. It drove and focused philosophical thinking. In the end, the precision of this frivolous high technology was a cornerstone for 17th-century scientific revolution, for 18th-century rationalism, and -- in the long run -- for the industrial and political revolution that brought in the 19th century.

16th and 17th-century clock-making was the work of technologists who danced to their own free-wheeling imaginations and esthetics -- technologists who were having fun. That kind of technologist really changes his world, and make no mistake -- these Baroque clock-makers set great changes in motion.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Maurice, K. and Mayr, O., The Clockwork Universe: German Clocks and Automata. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution and New York: Neal Watson Academic Publishers, 1980.

This episode has been rewritten as Episode 1294.

(From the 1911 Enclopaedia Britannica)

An old tower clock from Hidalgo, Mexico. This Baroque-style mechanism drives four eight-foot dials.