Printer's Marks

Today, a library wall heralds a new age of communication. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I heard an odd rumor during preparations for the Summit meeting here in Houston. Strange symbols are painted on the walls of the Reference room in the Rice University Library. The rumor was that government men wanted to paint over them. It wasn't true, but someone did ask if those symbols had arcane meanings. Could they offend delegates sitting in the room?

The question had come up before. When those hand-painted marks first appeared on the walls, people asked if they were signs of a Satanic cult. They're nothing of the kind, of course. They're old printer's marks. Actually, they look a lot like cattle brands. Early printers used them to identify their work.

A Printer's mark was a shorthand version of a more complete trademark called a printer's device. The device was a block print picture. The printer's mark was a simple little line drawing that reminds us of the device.

For example, one mark looks like a script letter "A" with three stars around it. The printers who used it were Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer. Their device was a pair of shields. The mark appeared on one of the shields in the device.

Fust was the wealthy goldsmith who bankrolled Gutenberg. When Gutenberg went bankrupt, Fust claimed the business for himself. So this mark takes us all the way back to 1457, and practically back to the birth of modern printing.

Here's another mark on the Library wall. It belonged to Charlotte Guillard. She took over her husband's print shop when he died in 1519. Then she taught printing to her second husband. when he died, she kept right on printing for 15 more years. Guillard's mark is a fancy circle with her initials in it. If it were a cattle brand, it'd be the Circle-CG. The first woman to run a print shop was Anna Rugerin. Like Guillard, she continued the trade when her husband died. That was only 30 years after Gutenberg. Even before that, Dominican sisters did typesetting.

The words on devices are more often written in local languages than in Latin. That's a surprise, because the language of books was Latin. Printers were literate, but few had studied the classics. They liked to print books in the language of the people who bought them. Right from the start, printers began taking knowledge out of the ivory tower and giving it to the public.

So these symbols on the wall aren't arcane at all. The first chapter in the history of the information age is written in these marks. What they really represent is the beginning of printing -- the beginning of the demystification of knowledge.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Masiak, C., On Our Marks: Symbols of Early Printers Adorn Fondren Reference Room. The Flyleaf. (published by The Friends of the Fondren Library, Rice University) Vol. 40, Issue 1, Fall 1989, pp. 2-7.

I am grateful to Kathleen Gunning, UH Library, for calling my attention to the foofaraw about the printer's marks at the Rice Library, for showing them to me, and for leading me to source material for this episode. I am gratful to Pat Bozeman, Head of Special Collections, UH Library, for her cogent discussions of the various printer's identifications.

The click-on image of Fust and Schoeffer's printer's device above is from Juan de Torquemada's, Exposito Psalteri, 1476, and provided by Special Collections, UH Library

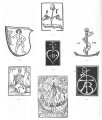

clipart images. Click on each of the three thumbnails above to see full-size images.

A comparison of a set of Printer's devices (on the left) with cattle brands (center), and with hobo signs from the American Depression years (right.)

The printers represented in the left-hand image are, from top center and moving clockwise: Englehard Shultis (Lyon, 1491), Manutius Aldus (Venezia, 1494), Thomas Anshelm (Pforzheim, 1506), Galliot du Prè (Paris, 1510), martin Flachs (Strassburg, 1501), Erhardt Rastold (Augsburg, 1494), and in the center, Bernardinus Stagninus (Venezia, 1494).