Blanchard

Today we join George Washington at a balloon ascent. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

French ballooning began in 1783 when two paper-bag makers -- the Montgolfier brothers -- began experimenting with hot-air balloons. They made the first manned ascent on November 21st, 1783, and eleven days later Alexandre Charles tested a manned hydrogen-filled balloon. And the game was on. Benjamin Franklin was in Paris at the time, and he watched several of the first flights. When someone asked what good they were, he gave his famous answer: "What good is a new-born baby?"

For a while everyone was flying balloons, and they were reaching altitudes that were limited only by people's ability to breathe rarified air.

A man named Jean-Pierre Blanchard first flew four months after the Montgolfiers. Blanchard became the first barnstormer -- he took his balloons on the road. That same year an expatriate American doctor named John Jeffries hired Blanchard to take him from England to France in a balloon. They didn't speak a common language, but that didn't stop them from reaching a fine dislike for each other. Still, they did manage to make the first aerial crossing of the English Channel.

Blanchard was an experimenter -- the first to drop animals in parachutes and the first to try to control his flights with sails and rudders. Then he took his act to America.

In Philadelphia he arranged to make the first American flight, on January 9th, 1793, nine years after the first Montgolfier flight. The Quakers had built a model prison that could be used to hide his takeoff from non-paying observers. He arranged to use it. Then he advertised in the Federal Gazette that people could watch the ascent for $5. He collected $400 and took off before a crowd that included President Washington himself. He landed in New Jersey and served his remaining wine to local farmers, who in return gave his balloon a lift into town on their wagon.

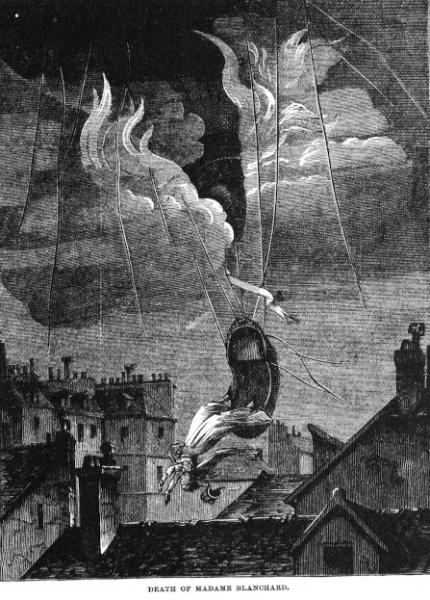

Blanchard died in Paris 16 years later, after suffering a fall. He'd made sixty flights, and then his wife continued in the business. Blanchard, by the way, used hydrogen in preference to hot air. His wife tried to improve the act with fireworks, and after 59 flights she perished by igniting the hydrogen in her balloon, over the Paris's Tivoli Gardens.

Well, that's pretty awful, but their game wasn't self-preservation -- it was excitement. And I'm convinced that technology is driven by people's excitements and enthusiasms far more than it's ever driven by the pursuit of purpose.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Rolt, L.T.C., The Aeronauts. New York: Walker and Company, 1966,

Crouch, T.D., The Eagle Aloft. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983, Chapters 2, 3, 4.

Jackson, D. D., The Aeronauts. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1981.

This episode has been revised as Episode 1351.

(From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia)

The Montgolfier brothers' first man-carrying balloon

(From the 1832 Edinburgh Encyclopaedia)

Blanchard's hydrogen balloon with paddles for navigation

(From Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1869)

Artist's image of the death of Madame Blanchard