The Erie Canal

Today, we ride 568 feet uphill in a barge. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A storm rises over central New York, and a ferryman, trudging beside his mule, hauling a barge through the Erie canal, sings:

Oh the Er-i-e is a-rising

And the liquor is getting low

And I scarcely think

We'll get a drink

Till we get to Buffalo.

The Erie canal is deeply grooved in our national awareness. It was a marvel -- a real marvel. Four of the Great Lakes lie above Niagara Falls -- Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie -- and they form a huge inland waterway with access to thousands of miles of shoreline: a waterway that touches Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, as well as New York. For our new country to be whole, East Coast commerce had to gain access to this waterway.

But the inland port of Buffalo, New York, at the east end of Lake Erie, is 363 miles from Albany on the Hudson River. Worse than that, Lake Erie lies 568 feet above the Hudson River. Connecting the two ends with a canal was no routine task.

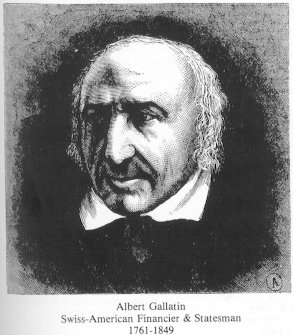

In 1801 Thomas Jefferson appointed a Swiss emigrant named Albert Gallatin as secretary of the Treasury. In 1808 Gallatin finished a proposal that we build a giant network of canals, including one between Lake Erie and the Hudson river. In 1810, the mayor of New York City, De Witt Clinton, picked the idea up. His support for the project got him elected governor of New York by a landslide in 1817. Construction of what was to be by far the longest canal ever built was ceremoniously begun on the fourth of July that year.

In 1801 Thomas Jefferson appointed a Swiss emigrant named Albert Gallatin as secretary of the Treasury. In 1808 Gallatin finished a proposal that we build a giant network of canals, including one between Lake Erie and the Hudson river. In 1810, the mayor of New York City, De Witt Clinton, picked the idea up. His support for the project got him elected governor of New York by a landslide in 1817. Construction of what was to be by far the longest canal ever built was ceremoniously begun on the fourth of July that year.

The task took 8 years and $7,000,000 to complete. It involved building 83 locks, an 802-foot aqueduct to carry shipping over the Mohawk river, and countless other innovations. Yet the job was done by four principal engineers who'd never seen a canal. Like so much early American technology, the work was done by amateurs whose zeal and self-assurance took them where angels would fear to tread.

The effect of the Erie canal on this country was stunning. Cargo that cost $100 a ton and took two weeks to carry by road could now be moved at $10 a ton in 3½ days. Horses and mules drew barges through the canal in end-to-end 15-mile shifts. And our ferryman sang the familiar song:

I've got an old mule, her name is Sal,

Fifteen miles on the Erie Canal.

She's a good old worker and a good old pal,

Fifteen miles on the Erie Canal.

The Erie canal completed one of Thomas Jefferson's dreams. It was a task that should've been beyond the engineers who did it. But they simply didn't know that.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Tarkov, J., Engineering the Erie Canal, American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Summer, 1996, pp. 54-57

This episode has been revised as Episode 1420.