In Praise of Humble Lint

Today highlighting a former fabric byproduct.

The University of Houston’s College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

The American Civil War was one of the deadliest conflicts in our history. Two sides, both convinced in their beliefs, faced off against one another: one pro-slavery and the other not. This often-pitted brother against brother, industrial north versus agricultural south. A recent re-evaluation of census records in 2024 puts the death toll at least 700,000 people. Most of them — around two-thirds — died not from bullets or cannon fire, but from disease. That may surprise us when we think about what happens in war.

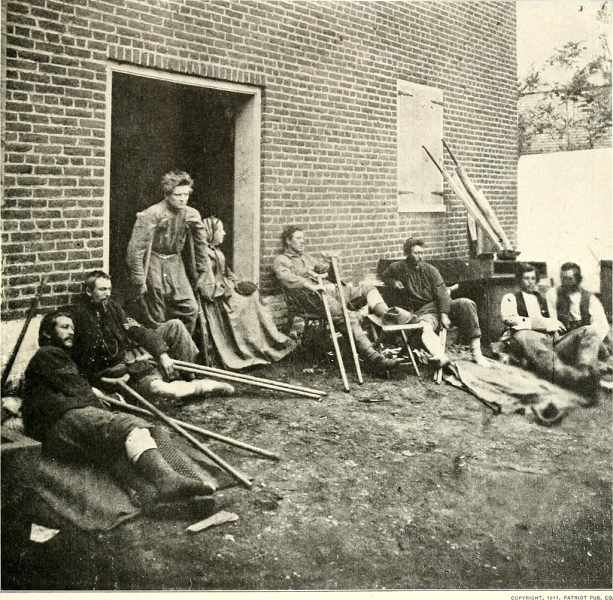

United States Sanitary Commission volunteer nurse, Abby Gibbons of New York City, and her patients at Fredericksburg, Virginia in May, 1864. They were a part of the Union’s awful toll of some 36,000 from the Army of the Potomac during the hard-driving Wilderness campaign. A private relief agency, it was created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861. The main function of its thousands of volunteers was to support sick and wounded northern soldiers. (Wikipedia – no restrictions)

During the four years of this conflict, doctors didn’t yet understand the true cause of disease. Louis Pasteur, in France, had shown in 1861 that tiny living things — what he called “germs” — were responsible. But that idea was still new.

Twenty years later, Robert Koch in Germany identified specific germs, or microbes, which caused specific illnesses. By then, however, it was far too late for those casualties of the American Civil War.

Doctors treated wounds the best they knew how. A soldier lucky enough to survive surgery for a small injury had a fair chance of recovering. But for those losing an arm or a leg, the risk of deadly infection was high. Germs spread everywhere, and no one really understood how to stop them.

Hospitals — whether permanent or temporary — were not clean by modern standards. Tents, borrowed houses, and field hospitals were over-crowded and dirty. Surgical tools weren’t sterilized. A doctor might finish treating one patient on a makeshift operating table made from a door, wipe his scalpel on his shirt sleeve or apron around his waist, and move straight on to the next case. The result was more infection and more death.

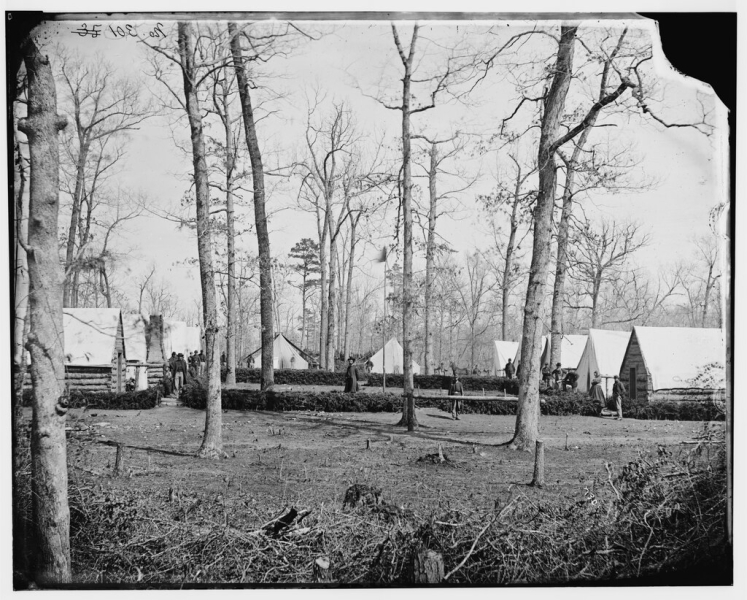

A contemporary view of the Union 3rd Division, 2nd Corps field hospital in the Army of the Potomac. Taken at Brandy Station, Virginia in 1864, it shows simple cabins built out of cut logs with canvas roofs laid out in an orderly pattern with streets between them. (Wikipedia – public domain)

Doctors did notice one thing: wounds that were covered seemed to heal better. That didn’t completely guarantee survival, but it did help. And this is where lint came in.

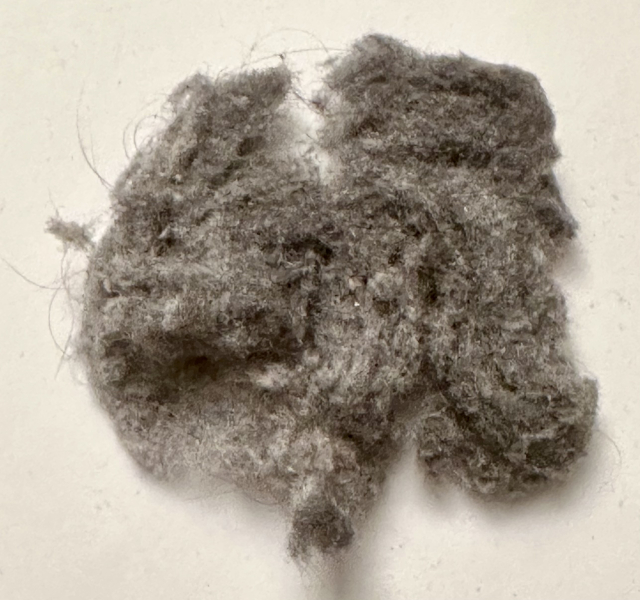

Lint — the fuzz you get from cloth — was collected and packed into wounds, and then moistened with water. This created a physical barrier, unknowingly protecting patient’s injuries from outside germs. It gave their bodies a better chance to heal.

But where did all that lint come from? You’ve probably seen movies of women’s gatherings during times of national crisis, such as the Civil War. These meetings weren’t just social — they were for work. Some knitted socks or sewed uniforms for soldiers. Others made lint. They did so by scraping old cloth into fibers — cotton, linen, or wool — all good sources. Once gathered into bags, the lint was sent to military doctors.

So, the next time you clean the lint filter in your home dryer, stop, if you will, for a moment. That soft pile of fibers you’re removing once played an important role in medicine and on the battlefield where it may have saved lives.

Lint

I’m Tom Callen on behalf of the University of Houston, and also interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme Music)

Some References

Barceló, Joan; Jensen, Jeffrey L.; Peisakhin, Leonid; Zhai, Haoyu (November 26, 2024). "New Estimates of US Civil War mortality from full-census records". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 121 (48)

Germ theory of disease - Wikipedia

___________________

This Episode first aired on October 15, 2025.