Aeroplane Structures

Today, we build old aeroplanes. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

I just found a forgotten book on my shelf: Aeroplane Structures, by two British engineers. It came out just after World War I ended. We find plenty of books about old aeroplanes. All about performance – speed, rate of climb, range – stuff like that. But not this one:

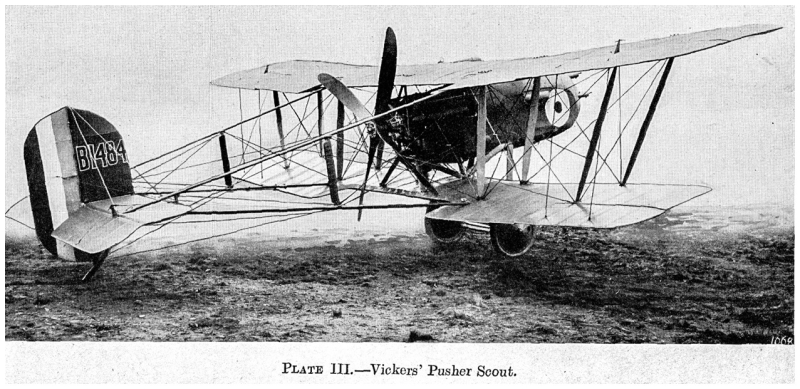

Here, I feel like I’m reading a structural engineering textbook. Same diagrams. Pages groaning with stress equations. We see beams and cross-braces. But very few pictures of finished aeroplanes. It could almost double as a bridge-builders’ manual.

And I realize: We tend to imagine those early aeroplanes as tossed together in someone’s workshop. They were not. Even the Wright Brothers’ notebooks bristle with tests and calculations. The few photos here show very primitive aeroplanes. But look again: those ‘planes are close kin to the great bridges and skyscrapers that arose in the generation before that war – with beams, cross-braces, and such.

Of course, science is behind engineering design. And science really had been addressing these new aeroplanes. Ludwig Prandtl did basic studies of aerodynamics in Germany before and during the War – analysis as well as experiments.

Germany had kept much of his wartime work secret. And they’d put many of his ideas to use. But the depth of Prandtl’s theoretical work saw the light of day only after the smoke of war had cleared.

He’d shown us exactly how air moved over wings. Knowing that, we could form more efficient wings and airfoil shapes. Aeroplane design was poised to make a huge leap forward between the Wars. And Prandtl’s work underlay much of that leap.

So, let’s look further. This books’ sections on how to shape airfoils are based on wind-tunnel studies – done by British engineers. They too knew a lot about lift and drag. But Prandtl had determined just how the air acted above and below an airfoil. He’d given theoretical depth to what wind tunnels might tell us.

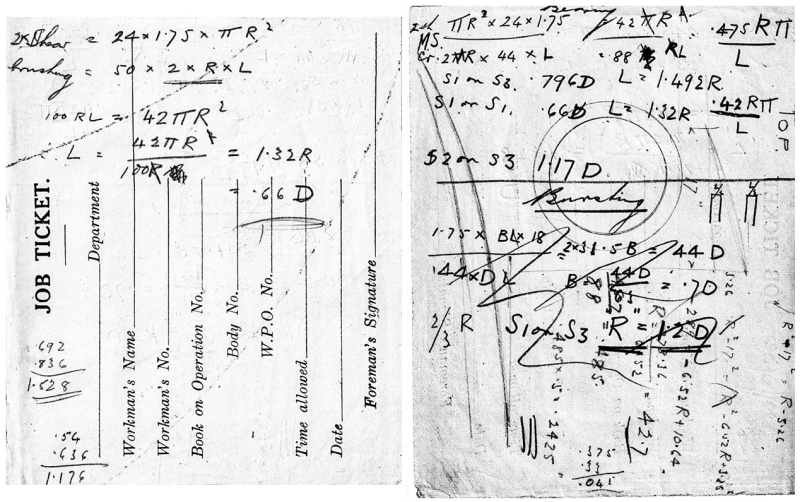

There’s more: I notice a name signed in this book: C. F. Hodson. So, I page through the book, looking for marginalia. What I do find is a slip of paper, tucked away in a part about how to select tubing.

It’s an old job ticket. Here, in Hodson’s handwriting, are calculations that might relate to tubing. And I wonder. Was he an aero engineer? Or did he just find this useful as a handbook. Either way, it was serving its purpose, even while airplanes were far outstripping it.

Old books are wondrous windows into our past, are they not? Past struggles begin to coalesce as we turn their pages. But we turn them at a cost: As we do so, new questions too often arise in place of the ones we’d meant to answer.

I’m John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we’re interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A. J. Sutton Pippard and J. Laurance Prichard, Aeroplane Structures, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1919 (1st ed.).

John H. Lienhard, “Ludwig Prandtl,” in Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. X, pp. 123–125.

lienhard_dictionary_scientific_biography_123-125.pdf

See too the Wikipedia article about Prandtl: Ludwig Prandtl - Wikipedia

All images are scanned from the Aeroplane Structures book except for the lift bridge photo. (It is my own.)

___________________

This Episode first aired on August 11, 2025.