Vera C. Rubin

Today, meet Vera Rubin. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory is just finished as I speak. It sits on a Chilean mountaintop. And it houses the largest camera ever built. It’s just started showing us patches of the sky in far greater detail than we’ve ever seen. But, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We’ll know more about it when this program reaches reruns. For now, let us leave the observatory ...

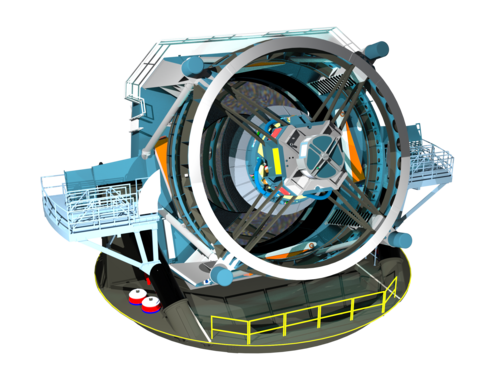

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory camera

... and meet its namesake, Vera Rubin. She was born in 1928, and, at age ten, was entranced by the stars. That fascination drove her past the terrible road-blocks women still faced when they chose science. She was still a child when she and her father built a crude telescope of her own.

But: Astronomy was especially unfriendly to women. So, Rubin had to thread her way through a maze. First, she studied at the women’s college, Vassar. (There, pioneering astronomer, Maria Mitchell, had been a founding faculty member.) And Rubin did well. Still, she was the only astronomy graduate that year.

Next, where to do graduate work? Princeton wouldn’t have a woman. Ah! But Cornell would! It taught minimal astronomy, but was very strong in physics. She worked with people like Hans Bethe. And Richard Feynman had just left. She also married and had the first of her four children there.

Rubin had secured her identity as an astronomer by the time she left Cornell with a Master’s degree. So, Georgetown accepted her to work on a PhD. There she studied with such famed astronomers as Gamow and Heyden. And her real accomplishments began taking form. Her dissertation showed that galaxies tended to clump together. Up to then, we’d thought they were simply scattered throughout the universe. Well, it took decades for that fact to gain traction.

.jpg)

Rubin measuring spectra in 1974

As she honed the idea, she learned many odd things about how galaxies moved. She kept overturning the common wisdom. So she faced a long uphill battle. Her research showed that galaxies had far more mass than they should have. That gave us crucial evidence for dark matter. And her work kept revealing weird features of galaxy dynamics.

One reason that Rubin’s work advanced the way it did, was her methodical nature. She knew how to question and test her ideas. How to make them move inexorably toward acceptance. She was patient. She was honest.

Now, as we wait to see what this new telescope will tell us, we also await another possible event, some four or five billion years from now – our Milky Way Galaxy colliding with Andromeda. As (Thank you, Vera Rubin) we fear it might.

I’m John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we’re interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

And more on Vera Rubin here: Vera Rubin

I mention Gamow and Heyden with whom Rubin worked at Georgetown. Here, I’ve linked their names to their Wikipedia pages.

Maria Mitchell | The Engines of Our Ingenuity

Cornell posts this article featuring Rubin’s presence on a US quarter.

See also: Rubin Observatory

or Vera C. Rubin Observatory - Wikipedia

The camera that occupies the Vera C. Rubin Observatory has an f-setting of 1.23 and a 10,310 mm focal length! For additional detail on the Camera, see: LSST Camera Arrives at Rubin Observatory in Chile, Paving the Way for Cosmic Exploration | Rubin Observatory It is to be served by a primary mirror, 27-1/2 feet in diameter.

Wikipedia article about the possible Milky Way/Andromeda collision.

I am indebted to retired Planetarium builder and director, Tom Callen, for his counsel. Callen also points out that the number of professional astronomers was very small when Rubin became one. By the mid-70s, much later, and long after our moon landing, there were still no more than 3000 astronomers in the US.

____________________________________

This Episode first aired on June 30, 2025