Physics in 1861

Today, a look at physics before our Civil War. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

Old books reveal far more than they are meant to reveal. Take this 1861 textbook – John Johnston’s Manual of Natural Philosophy. It’s the latest revision of a fifteen year old book. That old term natural philosophy was about to mutate into our word physics. So, what were students learning just before our Civil War? Look at its chapter titles: Mechanics, Hydrostatics, Pneumatics, Acoustics, Optics, Magnetism, and Electricity.

We made a huge technological leap forward after that war. And here we see where the builders of a new world stood – before they took that leap:

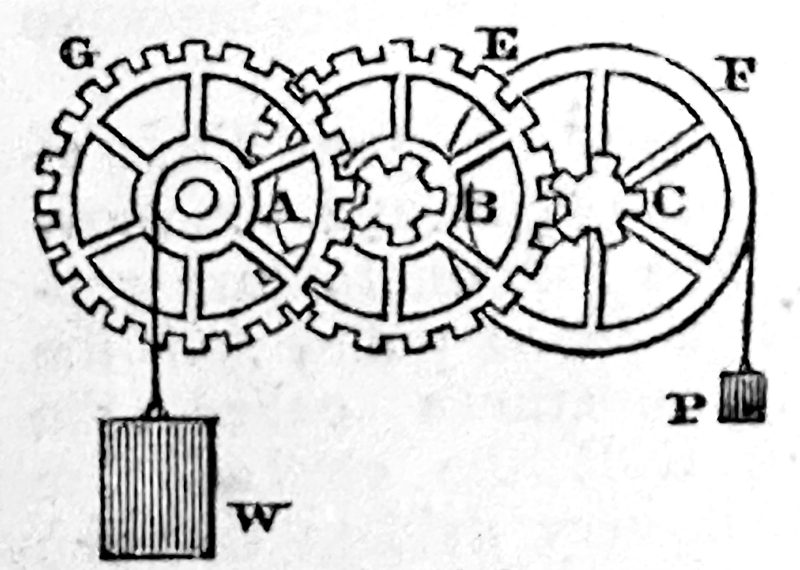

The Mechanics chapter is all about levers, pulleys, gravity, rotation. And it’s all done without a single equation – or even a formula. Can you imagine talking about acceleration without Newton’s force-equals-mass-times-acceleration?

The same is true of the Pneumatics chapter. Though here I catch myself. For Johnston does give us the concepts that precede mathematics. Today’s engineers could learn from this chapter, labored though it is. Much the same can be said of its chapters on Acoustics and Optics.

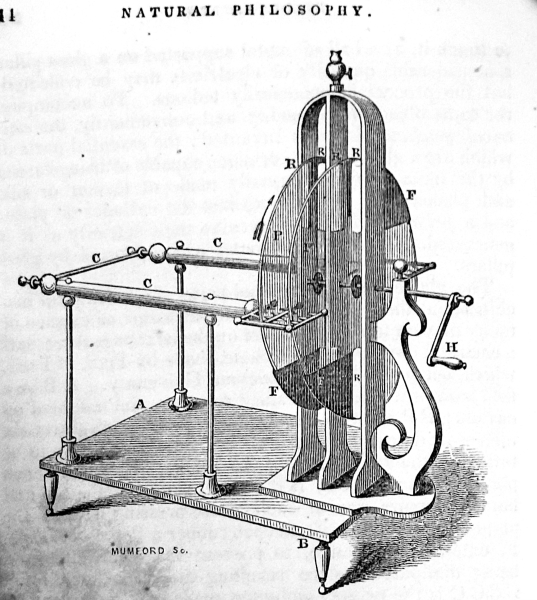

But – the two chapters on Magnetism and Electricity: They really catch my eye. These subjects were poised to change the future of humankind. And yet the chapter on Magnetism shows only the tricks we can do with magnets. It is fun. It even talks about Earth’s magnetic field. But a theory of magnetic fields -- that lay just over the hill, in the near future.

So we come to Electricity! Here we realize that this edition is just a reissue. It is not a revision. Electric telegraphs had matured just before its first edition. Yet Johnston didn’t recognize that in any edition. Science had shown that electric motors were possible, even before the first edition. People had already built battery-powered motors.

Of course, for an electric motor to be useful, it needed a dynamo to generate an electric current. Primitive ones existed. But workable ones would have to wait another sixteen years. Once more, the chapter brims with party tricks and curious phenomena. Some even hold the seeds of that unmentioned electric motor.

Oddly enough, books like this still echo in our grade schools. There we find teachers using its old examples to draw students into the study of science.

But this book is of an era when natural philosophy was just one branch of philosophy. It might’ve occupied a shelf with Thomas Aquinas or David Hume. It was still struggling to become the science that would reshape our world.

I’m John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we’re interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme Music)

John Johnston: “A Manual of Natural Philosophy,” (Philadelphia: Charles Desilver, 1861)

This Episode first aired on April 25, 2025