Filmstrips

(Theme music)

Today, filmstrips. The University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

Lately I’ve found myself thinking about filmstrips. In case that term doesn’t ring a bell, filmstrips were a medium used mostly in schools, from the nineteen-twenties through the nineteen-eighties. Basically they were a slide show of still images, sometimes with subtitles, but often with narration. The soundtrack came from a record player, if you remember those, or, later a cassette tape. The teacher advanced the slide manually, prompted by a tone. It was low-tech all the way.

Dukane record automatic filmstrip projector

Here's a typical filmstrip soundtrack. A mellifluous voice introduces our subject matter, in this case the writer Henry David Thoreau.

[Filmstrip soundtrack]

Now imagine some hand-illustrated images of the author, with maybe a few shots of Walden pond. No dissolves, fades or “Ken Burns effect,” his trademark use of slow panning and zooming. Filmstrips had none of that. They were the essence of minimalism.

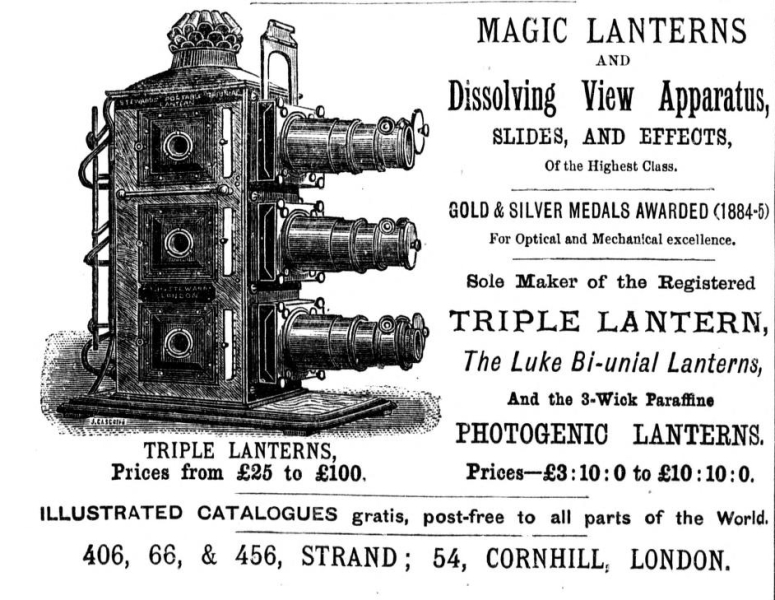

So how did they come about? The late 1800s saw the development of “magic lanterns,” projectors powered by gas or candle light. These were mostly marketed as entertainment, yet they made their way into the schools anyway. By World War I, Chicago public schools owned a collection of 8,000 lantern slides.

Unknown author - Colonial and Indian exhibition 1886, Public Domain

Thomas Edison predicted a visual future for teaching in the classroom. As he put it, "Books will soon be obsolete in the schools…it is possible to teach every branch of human knowledge with the motion picture.”

The filmstrip projector, invented in 1925, seemed to be a first step in that direction. Companies producing filmstrips ranged from giants like Disney, National Geographic, or Encyclopedia Brittanica, to one-man operations such as the Thomas S. Klise company of Peoria, Illinois. They covered every possible subject, from geography to manners to how to write a term paper. Filmstrips became a worldwide phenomenon and disappeared only with the advent of the videocassette in the 1980s, the DVD in the 1990s, then…streaming. As in streaming any time, anywhere, even on the phone in your pocket.

And therein lies the rub. “Content”—that’s the catch-all term for the ocean of videos, movies, books, blogs, photos, artwork, music, all on the internet—now requires virtually no effort to obtain. It comes to us with so little friction or cost it seems to sometimes beg the question of why we are seeking it at all. Perhaps Thoreau had the last word on the subject. He warned us to be wary of new technologies, calling them “an improved means to an unimproved end.” Hmm. I think I’ll resume waxing nostalgic about those humble filmstrips.

[Filmstrip soundtrack]

This is Roger Kaza, from the University of Houston, where we’re interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The filmstrip voice is that of Thomas S. Klise, also known as author of the epic novel, The Last Western. His filmstrip company was founded in 1966. Thomas Klise/Crimson Multimedia is now based in Connecticut. Thanks to Molly Klise for her assistance with this episode. “The teacher advanced the slide.” This was the usual procedure, although some of the later machines were built to detect a very low pitched tone on the soundtrack which would auto-advance the slides. As mentioned, some early filmstrips were silent and came with subtitles. There was yet another variation where the teacher would read a prewritten script while advancing the slides. “Filmstrip” is so named because the slides were packaged as a continuous roll of 35mm film, rather than individually mounted slides. They were thus very portable and came in a small round container.

Wikipedia article on filmstrips.

A short history of filmstrips.

Scholarly look at filmstrip archives.

YouTube video about filmstrips.

Internet archive of filmstrips.

This episode first aired February 11, 2025