New Year Fireworks

by Karen Fang

Today, we ring the new year in with a bang. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

For Chinese New Year, my family and I will wear red, make dumplings, and children will collect money from their elders. We'll gather with others to watch a lion dance, and all our celebrations may be punctuated with the bang of fireworks and firecrackers.

Fireworks, like paper and printing, are a Chinese invention. As early as 200 BC, Chinese threw bamboo stems into fire for fun, because the small explosions made loud sounds. After gunpowder was invented, in the ninth century, small sheets of paper rolled in the shape of bamboo were filled with gunpowder and lit with a fuse. By then fireworks were regularly used in military and ceremonial events, to showcase the Chinese Emperor's power. But they also remained part of civilian Chinese culture. Commoners could buy simple fireworks from vendors at market stalls, just like they picked up fresh pork, dried tea, and fresh steam buns.

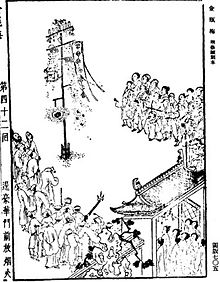

Fireworks display, from a seventeenth century edition of Ming dynasty literary work,Jin Ping Mei (Reproduced in Joseph Needham (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. Page 142.)

Photo Credit: Wikipedia.

Firecrackers' auditory excitement gained additional visual spectacle when Chinese fireworks added color. As early as 200 AD, Han dynasty scholars knew which chemicals tinted smoke and fire. By the eighteenth century, Chinese pyrotechnics were the envy of Europe, which by then was also manufacturing fireworks. But Western fireworks still could not equal the rainbow of colors that Chinese varieties had achieved for centuries.

Today chemists, scientist, engineers, and pyrotechnicians all know the recipes that make modern fireworks burst with such vibrant hues. Yellow comes from sodium; green from barium and copper; orange from calcium, and red from strontium and lithium. The brightest, sparkliest silvery light comes from aluminum.

For me, however, each time I am dazzled by fireworks, I admire both the spectacle and this proud reminder of Chinese contributions to civilization. So often innovations in science and technology are about establishing power. We want bigger, louder, and more bang for the buck.

Firecrackers burst as part of a lion dance performance. "Lions and Firecrackers."

Photo Credit: flickr by Daveography.ca is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Fireworks and firecrackers aren't innocent of this compulsion, but they began as something simple and festive. Chinese culture loves rènao, "heat and noise." Rènao can be heard in the clatter of chopsticks and the sizzle of a wok--especially when celebrating with family and friends. Early pyrotechnics started with this simple urge forrènao, so every time I enjoy fireworks I thrill not just at a Chinese invention, but especially because this particular invention reminds us that power and innovation doesn't have to hurt, destroy, or exploit.

Lunar new year is celebrated by many cultures, and of all Chinese New Year traditions fireworks and firecrackers are a custom adopted by people across the globe. So whether your new year begins on January 1 or by the lunar calendar, and whether you light fireworks on July 4, Guy Fawkes, Bastille Day, Diwali, or just because, rememberrènao. Fireworks started with the joy of being together.

Xin nian kuai le! Gong hei fat choy! Happy lunar new year!

I'm Karen Fang, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This episode was first aired on February 1, 2022