The Power of Pink

by Karen Fang

Today, the power of pink. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We tend to think of pink as a feminine color, but that wasn't always the case. In Europe before the twentieth century, it was common to dress boys in pink and girls in baby blue. This was because pink, as a shade of red, was deemed the color of ruddy potency, while blue has a long Christian association with virginity.

Louis Carmontelle, Portrait of Paul Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach, 1766

Photo Credit: Wikipedia.

By the eighteenth century, however, pink acquired its links with femininity, maidenhood and sexual attraction. The English beauty, Lady Hamilton, loved to dress in pink to show off her creamy complexion, and Louis XV's mistress, Madame de Pompadour, so loved a particular rosy shade of porcelain that the shade was named for her. Thomas Gainsborough's famous 1794 painting of a young woman swathed in pink silk, popularly known as Pinkie, epitomizes this ideal of nubile sensuality.

Pinkie (portrait of Sarah Barrett Moulton), 1794, courtesy of Huntington Library." width="70%">

Thomas Gainsborough, Pinkie (portrait of Sarah Barrett Moulton),

1794, courtesy of Huntington Library.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia.

It's this later connection of pink with femininity that American industry seized on by the 1950s, as postwar manufacturers began gendering items as a way of convincing consumers that they needed different versions of basically the same commodity. Suddenly there were pink plastic telephones, hair brushes, and hand luggage. Pink also revived a cult of domesticity disrupted by war, helping impose separate spheres so that women who had entered the workforce during war would now vacate jobs for returning men.

Pink doesn't appear on the electromagnetic spectrum, and without horticultural breeding rarely appears in nature. Yet it's one of the few shades with such cultural impact that it has its own name. We say "pink" when it's just a lighter shade of red; for other hues, we get by with "light blue" or "light green." Pink has such global currency that Japanese uses an English loan word, pinku, for the blush of cherry blossoms. (Pink is also, ironically, the Japanese term for the film genre that Americans call a "blue" movie.)

But while pink's undertones of delicacy and femininity suggest preciousness, histories like the postwar gendering of pink also show how preciousness withholds power. In Nazi concentration camps, homosexuals and others held for purported moral deviance were forced to wear pink triangles. In the 1980s, prison administrators influenced by psychology research experimented with painting prison cells pink, in hopes of reducing aggression. While some sites reported calmer populations, others feared potential riots from pink's perceived emasculation.

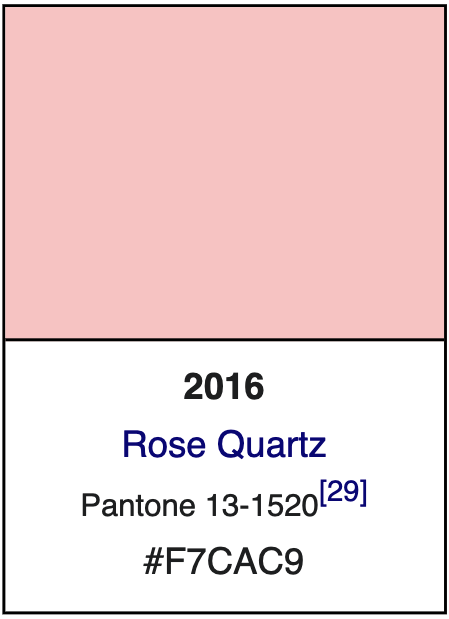

Today, however, LGBTQ groups have reappropriated pink triangles as emblems of pride, as have women's rights and related movements, like breast cancer awareness, which choose pink as the banner of their collective identity. Gender conventions about pink in commodities and consumer culture also are less stringent. In 2015 the chemical company Pantone named a dusky, subdued pink called "Rose Quartz," but best known as "Millennial Pink," as 2016 Color of the Year.

Rose Quartz, Pantone 13-1520, #F7CAC9

Photo Credit: Pantone.

Pink may still have hints of "sugar and spice, and everything nice," but that apparent innocence masks a complex history of power, both for and against. Forever a color rich in contradiction, pink is always more serious than it appears.

I'm Karen Fang, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Puja Bhattacharjee, "The Complicated Gender History of Pink" cnn.com, January 12, 2018.

Julie Irish, "The Surprisingly Dark History of the Color Pink" Fast Company, September 28, 2018.

Barbara Nemitz, Pink: The Exposed Color in Contemporary Art and Culture 2006.

This episode was first aired on May 25, 2021