The Converging Literacies of the Digital Age

Today, we read old newspapers. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The internet is killing the newspaper. You've heard this accusation before, and it makes a certain sense. If you get your news online from various sources; if you can look for a job or sell a car online; if you can see what people are up to on social media, why would you pay for a newspaper? We seem to be at a watershed in social literacy: a locally produced newspaper is a relic of the past that took root before computers, before television, even before radio. So we should just it let go the way of horse-drawn plows and hoop skirts.

But here's an interesting irony of the digital age: the newspapers of the past are in greater circulation than ever before, thanks to the digitization of newspaper archives. Now you can go back in time and read the news from a century ago more easily than even its original readers could.

I know this, because I've been reading old editions of the Evening Sentinel, the local newspaper put out in Centralia, Illinois, a town with less than 13,000 people. I've been looking for news about my father's father, a man I never knew. In fact, when he died, I was planned as his replacement. So he'd always just been a photograph and a few stories to me - until now.

My grandfather James W. Armstrong in 1915 (family photograph)

Thanks to the chatty nature of local newspaper culture, James Armstrong is coming alive to me as a favorite son of this little Illinois town. I read how he was the only student at his high school to score honors at a regional competition in 1914 - second place for the boys' solo. No great shakes, but the paper crows about it on the front page. In 1918, the Sentinel reports how he's left college to sign up for the Army - again, this is front page news. How, upon his return to college, he led Northwestern against the University of Chicago in debate. How later he's become a successful teacher at Northwestern, popular with the students; how he was appointed Dean of Men there in 1924, and came back to speak at his high school homecoming to shouts of "Jimmie! Jimmie!" The paper later tells readers to stay tuned for Dean Armstrong's radio addresses.

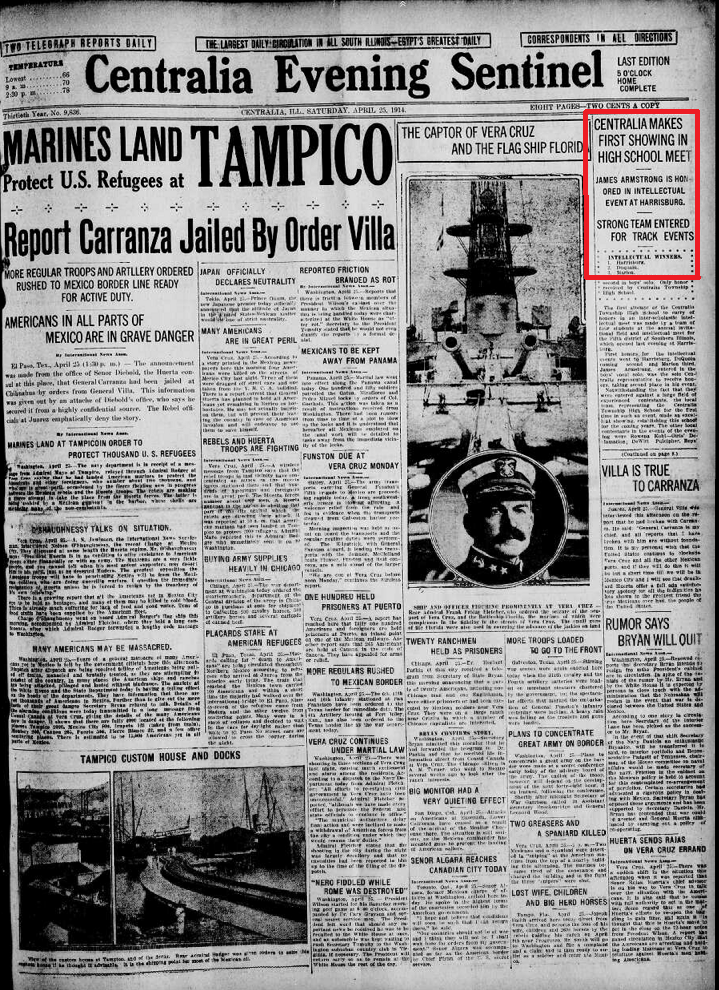

The Evening Sentinel for Saturday April 25, 1914 showing my grandfather's high school competition alongside the world news on page 1.

Photo Credit: NewspaperArchive.com

The local newspaper fed its readers' need for news of all kinds. The combination of international and local stories on the front page can be jarring. My grandfather's second-place solo victory is inches away from a dramatic report of the US invasion of Vera Cruz during the Mexican Revolution. Inside the paper, a "comings and goings" column sets a pretty low bar for newsworthy items. I see my father made the paper simply by coming to see his grandfather; Dad was six months old at the time!

The truth is, new forms of media shift the information landscape, they don't annihilate their predecessors. Radio lived alongside newspapers, then television joined them. Now the all-devouring internet has arrived, on which you can read old newspapers and new, hear live and re-broadcasts of radio programs like this one, and even watch television shows.

So the question isn't: what's the best medium? To my mind, it's: into what kind of "community" are we evolving in the digital age?

I'm Richard Armstrong at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A surprising number of newspapers can be searched in digital form now on such commercial websites as https://newspaperarchive.com/.

The Center for Research Libraries Global Resources Network hosts this International Coalition on Newspapers (ICON) with information by country at http://icon.crl.edu/digitization.php.