Purple Men

Today, we see purple. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

What human activity could push a beautiful shellfish to the brink of extinction? It's not pollution as you might think, but the color purple.

Mysterious, hypnotic, and coveted for its rareness, the color has represented royalty for thousands of years. The ancients obtained a photo-reactive dye for cloth from sea snail excretions, which changed color from yellow to purple when exposed to sunlight and air. They would brutally crush over 10,000 individual snails of the genus Murex to extract one gram of the dye, making it almost priceless. The word "purple" comes from "purpura", the Latin word for the sea snail, as does the name Phoenicians, the Purple Men of Tyre in Lebanon that were the ancient dyers.

Tyrian Men Photo Credit: Ancient History Encyclopedia

In Roman times, on pain of death, only the Emperor could wear an entire purple toga. Queen Cleopatra of Egypt recognized the color's seductive qualities and had the perfumed sails of her royal barge dyed purple, inspiring Julius Caesar to establish the color in Rome.

Hercules and the Discovery of the Secret of Purple Photo Credit: Wikimedia

After 1450 AD, Tyrian Purple went into precipitous decline from the over-harvesting and collapse of the Murex species. Mountains of crushed mollusk shells have been discovered by archeologists near modern Tyre. Throughout the ensuing centuries dyer's guilds in Europe used natural plant and insect dye-stuffs for red and blue cloth, but true purple disappeared. Red became the color of distinction, as in the robes of the Catholic Cardinals.

Brandhorn Bolinus brandaris Photo Credit: Wikimedia

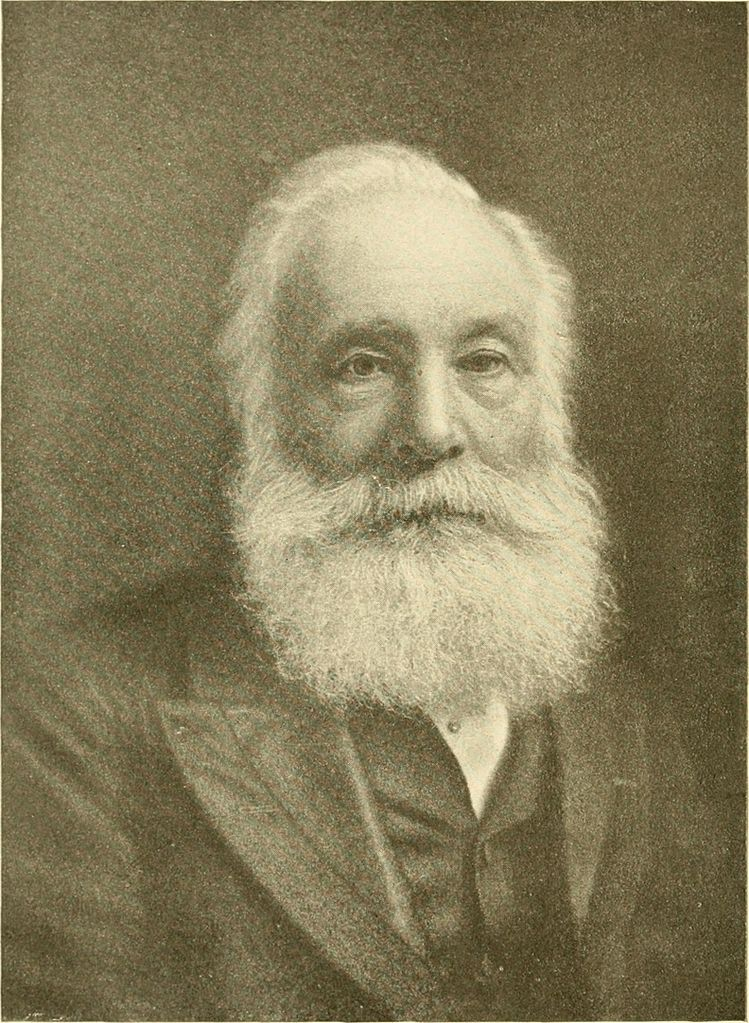

But in 1856 William Perkin, a gifted young chemist in England, made a chance discovery from a lab process using coal tar. Instead of throwing away the blackened substance that remained he was curious and distilled it. The result was a brilliant purple dyestuff that on silk and cotton was permanent and colorfast. He soon left the Royal College of Chemistry and began production in a small family factory, naming his color Perkin's Mauve after a French flower of the same color, in order to court the textile industry. Within three years a European fashion frenzy for purple erupted; even Queen Victoria ordered an all mauve dress for a royal celebration.

William Perkin Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Suddenly English, German and French chemists competed to see how many coal-tar dyes they could rapidly discover, grounding the field of chemical engineering for textiles and pharmaceuticals. Within a decade organic dyestuffs were rarely ordered, replaced by the new synthetic aniline colors the world still uses today.

Though the Mediterranean mollusks were driven toward extinction, the ancient Aztecs sustainably "milked" their sea snails, returning them to the waters, so a natural purple dye still exists today in Mexico. Modern industry has democratized this regal color, so now we are all entitled to purple, without waiting for it at a snail's pace, - or at the cost of their lives.

I'm Celeste Williams at the University of Houston where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Garfield, Simon, Mauve, WW. Norton Publishers, New York, London, 2000.

Finley, Victoria, Color, Random House Publishers, New York, 2002

Harley, R. D., Artists' Pigments c. 1600-1835, Butterworths Scientific Publishers, London, Boston, 1982.