A War of Concrete

Today, a portable port saves the day. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

By 1941, Hitler'd given up on the idea of invading Britain. So German planning shifted to defending Europe's long Atlantic coastline. Gradually, this plan would involve pouring over 17 million tons of concrete to build massive gun emplacements and defense works stretching from France to Norway. Fortress Europe, it was hailed.

Hitler was convinced an Allied invasion would have to strike at a significant port. Otherwise, how could the Allies expand any breach into a major thrust into Europe? They'd need a port's facilities to supply their invasion force. This assumption would prove to be a fatal miscalculation. As the war dragged on, the Germans intensified their construction. By early 1944, they more than doubled the monthly amount of concrete being laid in defense works.

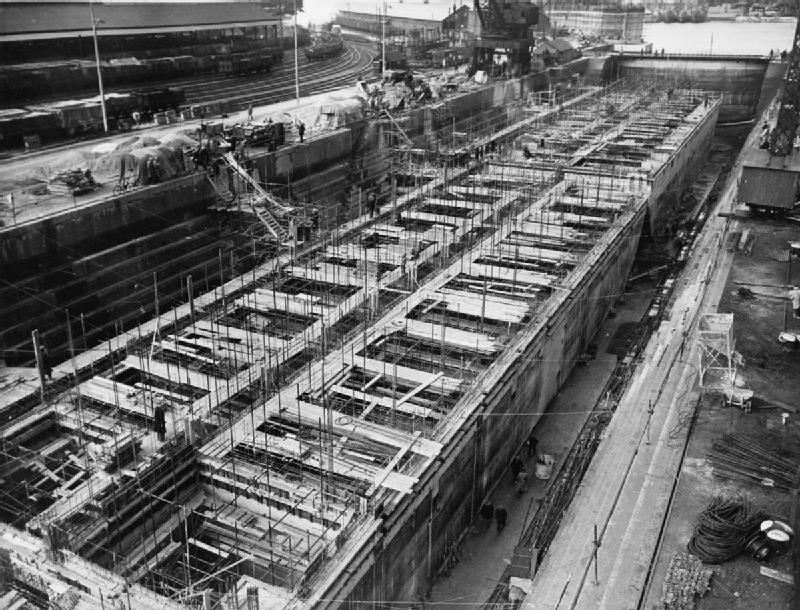

Phoenix caissons in construction, Weymouth UK April 1944 Photo Credit: Wikipedia

The Allies chose to land on the beaches of Normandy precisely because there was no major port there. But they exploited Hitler's assumption by mounting a successful diversionary campaign: they made it appear the port of Calais would be their target. In the meantime, they got busy pouring a lot of concrete of their own. They had to solve the problem of how to create a harbor sufficient to supply the invading army. Without it, their troops would be thrown back into the sea.

The solution was known as the Mulberry harbor, one of many brilliant innovations brought out for D-Day. This involved creating a series of breakwaters, first by sailing old ships into place and scuttling them. Next, came huge concrete caissons six-stories high, known as "Phoenix" units. These were floated over and sunk into place to reinforce the scuttled ships. With such a sturdy breakwater now sheltering the shore, pontoon piers were set up, allowing ships to unload their cargos far from the sandbars. These floating piers would rise and fall with the powerful coastal tides.

The British harbor in September 1944 Photo Credit: Wikipedia

The construction of the huge Phoenix caissons was one of many well-kept secrets during the months before D-Day. Massive amounts of concrete and steel were used in making them at sites all over Britain. Then they were towed by sea to the South Coast and sunk to hide them from German reconnaissance. By the afternoon of D-Day, over 400 components for making two Mulberry harbors set out for Normandy, comprising one and a half million tons of material. By mid-June the Mulberries were finished, with an American harbor at Omaha Beach and British one at Gold Beach. But then a terrible storm destroyed the American harbor on June 19. However, the British Mulberry was repaired and held up for five crucial months. It was only supposed to last for three. Two and a half million men, a half million vehicles, and 4 million tons of supplies rolled into France along that harbor, which became known defiantly as Port Winston (named after Britain's undaunted leader, Winston Churchill).

View of the pier at Omaha before the storm Photo Credit: Wikipedia

We celebrate the heroism of those who charged up the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944. But when the action shifted from combat to support, those hard-won beachheads still remained vital to the allied effort. Allied engineers had turned the biggest logistical problem of the invasion into a concrete victory.

I'm Richard Armstrong, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Note: The term "Mulberry" was an arbitrary codename, one of many used to obscure the real subject under discussion.

Sources:

Hartcup, Guy. 2011. Codename Mulberry: The Planning, Building, and Operation of the Normandy Harbours. Pen and Sword.

Messenger, Charles. 2004. The D-Day Atlas: Anatomy of the Normandy Campaign. Thames & Hudson.

Stanford, Alfred. 1951. Force Mulberry: The Planning and Installation of the Artificial Harbor off US Normandy Beaches in World War II. Morrow.

Wilt, Alan F. 2004. The Atlantic Wall 1941-1944: Hitler's Defenses for D-Day. Enigma Books.

Online Sources:

This website provides diagrams and photos in detail: http://www.thinkdefence.co.uk/shore-logistics-d-day-beyond/d-day-plus/

This video shows aerial drone photography of the site of the British Mulberry's remains as they are today off Arromanches: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWi3EHXiWGI

This video shows virtual reality reconstructions of Port Winston in its heyday: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_2sTpGEswA

This older British short documentary shows contemporary film footage: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHnyzAODbaA